Behind the Conflict: Shaping Modern Palestine

What was Palestine before Palestine was born? The Changing Borders of a region that have locked two Peoples into a seemingly endless Conflict.

Behind the Conflict: Shaping Modern Palestine

In order to understand the complex situation that has been plaguing the Palestinian region for years, it is wise to go back and glance at what the same region looked like before the creation of the State of Israel and the State of Palestine.

Today’s Palestine is a geographical region that embraces both states. However, it was not always so, and such an understanding of Palestine was only born about 100 years ago. Indeed, the geographical boundaries of the region were never unequivocally defined until 1922.

They have expanded to include territories beyond the Jordan River to the East, up to the Lebanon mountain range to the North, and part of the Sinai Peninsula to the South.

During Roman rule, the division into Palestina Prima, Palestina Secunda, and Palestina Tertia encompassed territories that also included parts of today’s Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia (Lewis, 1980, p.3,4).

This article aims to outline the historical evolution that shaped the contemporary conception of the Palestinian region, thus providing the background material for understanding the origin of the persistent conflict that has turned the region inherently unstable and Insecure since its contemporary conception. This will be achieved through the analysis of:

- The Palestinian region under the Ottoman Empire.

- The 3 main developments leading to the region’s transition from Turkish to British hands - i.e. the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, the Sykes-Picot Agreement, and the Balfour Declaration.

- The League of Nations Mandate System.

- The British Mandate over the Palestinian region that constructed the modern conception of Palestine.

Retracing these pivotal circumstances is intended to suggest some of the drivers that contributed to the emergence of the Israeli–Palestinian and Israeli-Arab conflicts.

1. An Indefinite Region: Palestine under the Ottoman Empire

From an administrative perspective, the Palestinian region was never united until the British Mandate of 1920.

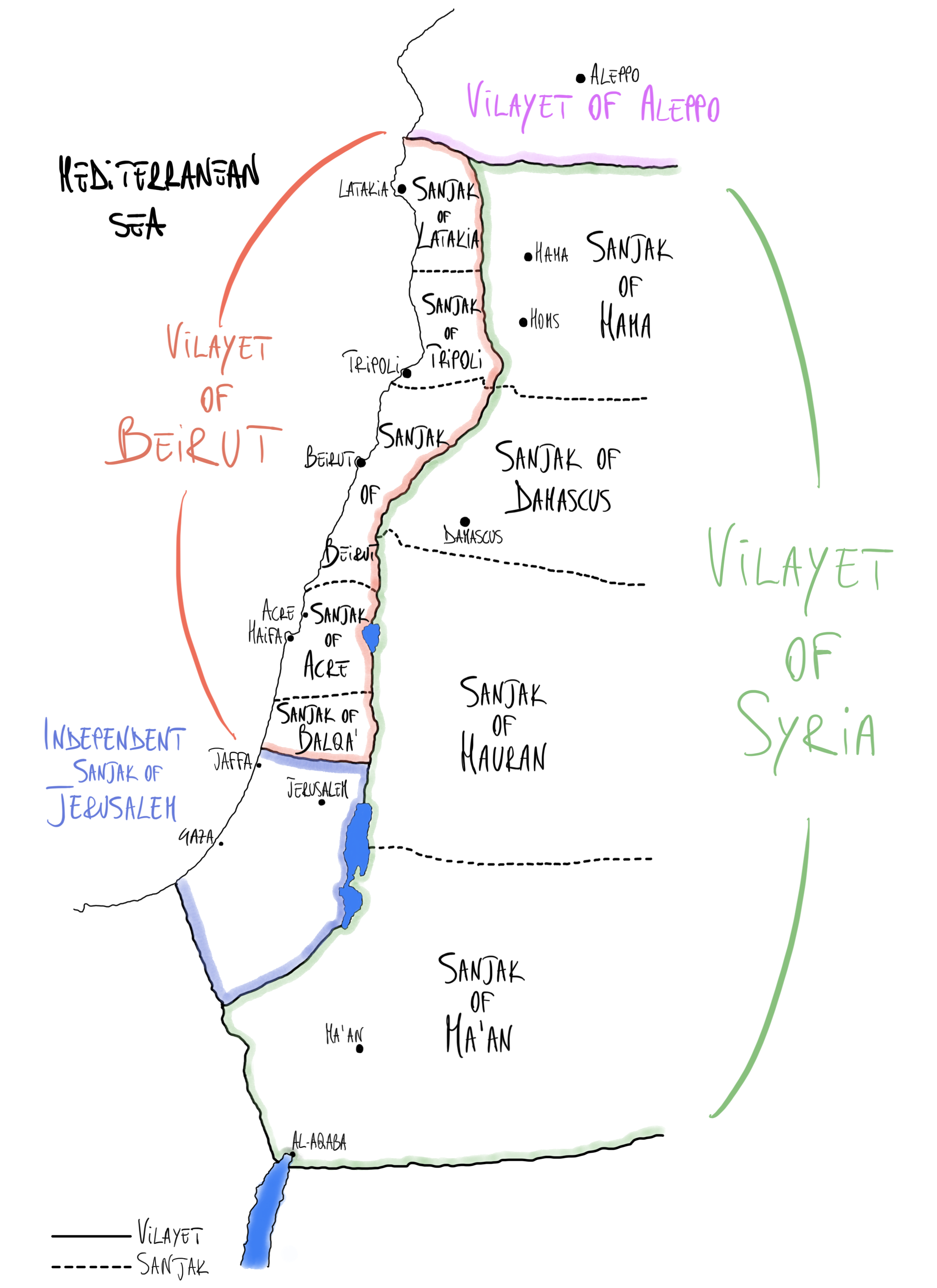

Before the British Mandate, the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922) was divided into administrative districts called Sanjak. These Sanjaks then formed larger administrative provinces called Vilayets (Arabic: Wilaya) (Smith, 2017, Ch.1).

- In the 19th century, the Palestinian region was therefore divided into five Sanjak: Gaza, Nablus, Jerusalem, Lajun, and Safad. These Sanjaks were part of the Vilayets of Syria, which were governed by the city of Damascus.

- At the beginning of the 20th century, following several transformations, Palestine still appeared divided. Northern Palestine consisted of two districts, Acre and Nablus, which were part of the larger Beirut province. In the southern part of Palestine, the independent governorate of Jerusalem was established, directly linked to the central administration. (Map 1)

2. The Road to the British Mandate

Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the awarding of the Palestinian Mandate to Great Britain can be traced through three key stages:

- The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence

- The Sykes-Picot Agreement

- The Balfour Declaration

2.1. The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence

During World War I, Britain aimed to shape the post-war global landscape.

As part of this effort, the British High Commissioner to Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, engaged in extensive correspondence (1915-1916) with Hussein Sherif of Mecca, the most eminent Arab leader at the time.

These letters, interchanged in Arabic, explored the prospect of the Arabs instigating a revolution within the Ottoman Empire, which, in turn, could assist the British Empire in its war efforts. In exchange, Hussein requested a commitment from the Empire to recognize Arab independence and the establishment of Arab states (Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, G.C.M.G., His Majesty’s High Commissioner at Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca July, 1915-March, 1916, [Cmd. 5957]).

The correspondence expressed the Arabs’ preference for “British assistance to any other” and delved into specific details regarding the borders that would impact the newly emerging Arab nations (Smith, 2017, Ch.2).

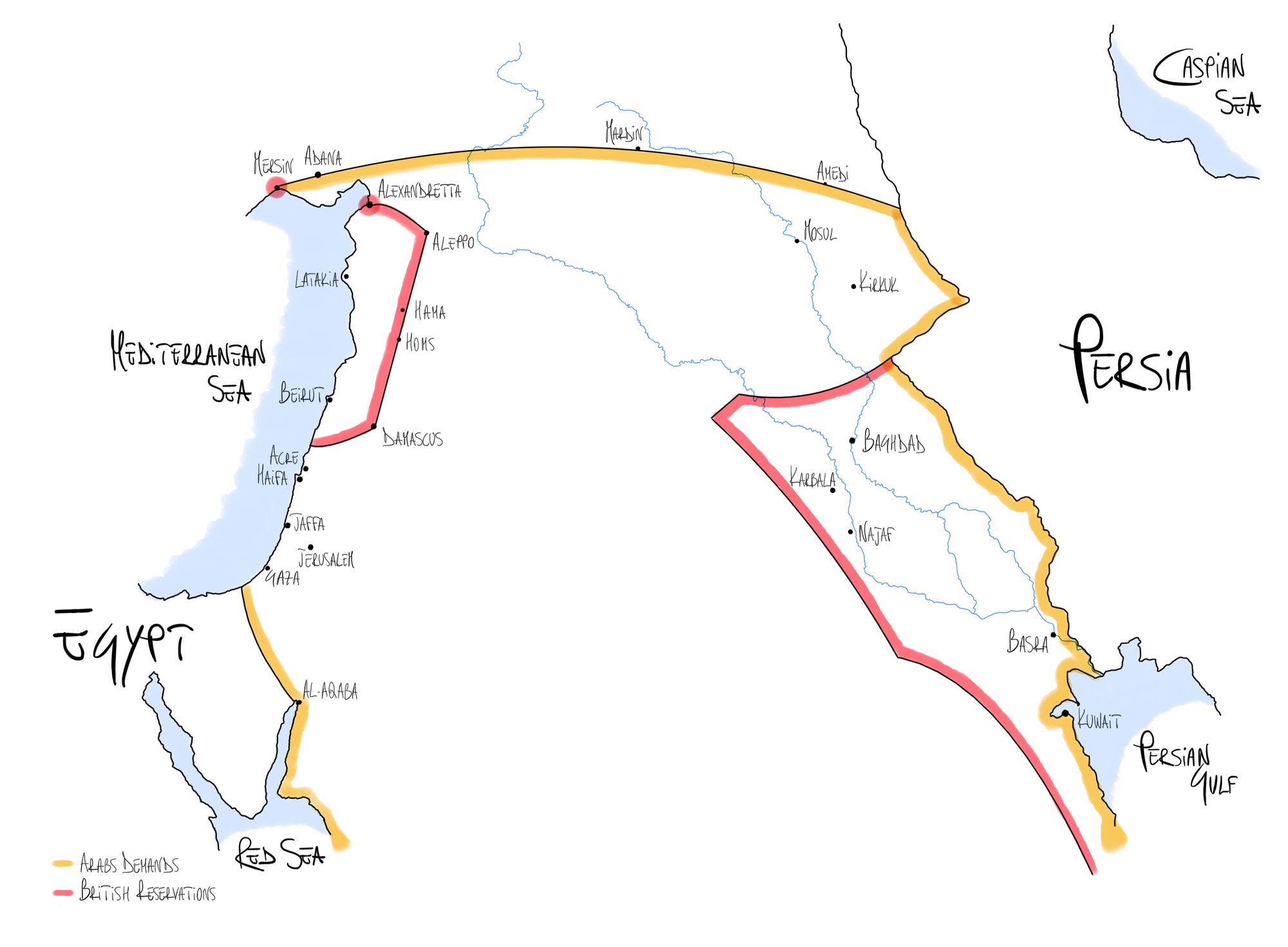

Specifically, it read that demands were for territories bounded:

“On the north by Mersina and Adana up to the 37° of latitude, on which degree fall Birijik, Urfa, Mardin, Midiat. Jezirat (Ibn ‘Umar), Amadia, up to the border of Persia; on the east, by the borders of Persia up to the Gulf of Basra; on the south, by the Indian Ocean, (with the exception of the position of Aden to remain as it is; on the west by the Red Sea, the Mediterranean Sea up to Mersina” (Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, G.C.M.G., His Majesty’s High Commissioner at Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca July, 1915-March, 1916, [Cmd. 5957]). (Map 2)

However, the British initially rejected discussions on borders as appearing to be “premature” at that stage of the war. Following dissatisfaction on the part of the Arab counterpart, Britain expressed its support for Arab independence within the proposed borders, yet exercised a reservation over the Mediterranean coastal territories:

“The two districts of Mersina and Alexandretta and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded from the limits demanded.

With the above modification, and without prejudice to our existing treaties with Arab Chiefs, we accept those limits.

[…] With regard to the vilayets of Bagdad and Basra, the Arabs will recognise that the established position and interests of Great Britain necessitate special administrative arrangements”. (Map 2)

The literal exclusion of the Palestinian region from the British-reserved territories is clearly evident in these words.

- There have been phraseological attempts to include Palestine in such territories. Indeed, although the original English version uses the term District to point to Damascus and the other towns, the Arabic version sent to the Sherif of Mecca employs the term Vilayet indicating the wider territorial extension of the western part of the Vilayet of Syria (Secretary of State for the Colonies, 1939).

- Conceptual attempts to justify the exclusion of Palestine from the territories allocated to the Arabs have instead been made by Winston Churchill in his 1922 White Paper, where he asserted that the British promise for Arab territorial independence support

“was given subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the west of the District of Damascus. This reservation has always been regarded by His Majesty’s Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir. Henry McMahon’s pledge”.

The phraseological attempts were later refuted by a Committee’s Official Report presented by the British themselves in 1939:

“His Majesty’s Government’s contention that the phrase ‘the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo’ included the whole of the Vilayet of Syria is untenable. It rests on the theory that district is equivalent to vilayet, which, in the light of the context as well as of common sense, is demonstrably false” (Secretary of State for the Colonies, 1939, Annex E(3)).

Yet, the same British Report was clear in emphasising Churchill’s version:

“The view of His Majesty’s Government has always been that the phrase ‘portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Kama, Homs and Aleppo’ embraced all that portion of Syria (including what is now called Palestine) lying to the west of inter alia the administrative area known as the ‘Vilayet of Syria’” (Secretary of State for the Colonies, 1939, Annex B(18))

considering that

“the term Syria in those days was generally used to denote the whole of geographical and historic Syria, that is to say the whole of the country lying between the Taurus Mountains and the Sinai Peninsula, which was made up of part of the Vilayet of Aleppo, the Vilayet of Bairut, the Vilayet of Syria, the Sanjaq of the Lebanon, and the Sanjaq of Jerusalem. It included that part of the country which was afterwards detached from it to form the mandated territory of Palestine” (Secretary of State for the Colonies, 1939, Memorandum on the British Pledges to the Arabs (3)).

Although these correspondences did not constitute written treaties and therefore did not create legal obligations, they eventually led to the dissatisfaction of the Arab counterpart since the territorial partition did not align with their expectations.

2.2. The Sykes-Picot Agreement

The post-war partitioning of the Ottoman Empire’s lands was a subject of planning among European nations.

Notably, a confidential dialogue between France and Britain, culminating in the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, played a pivotal role in this process.

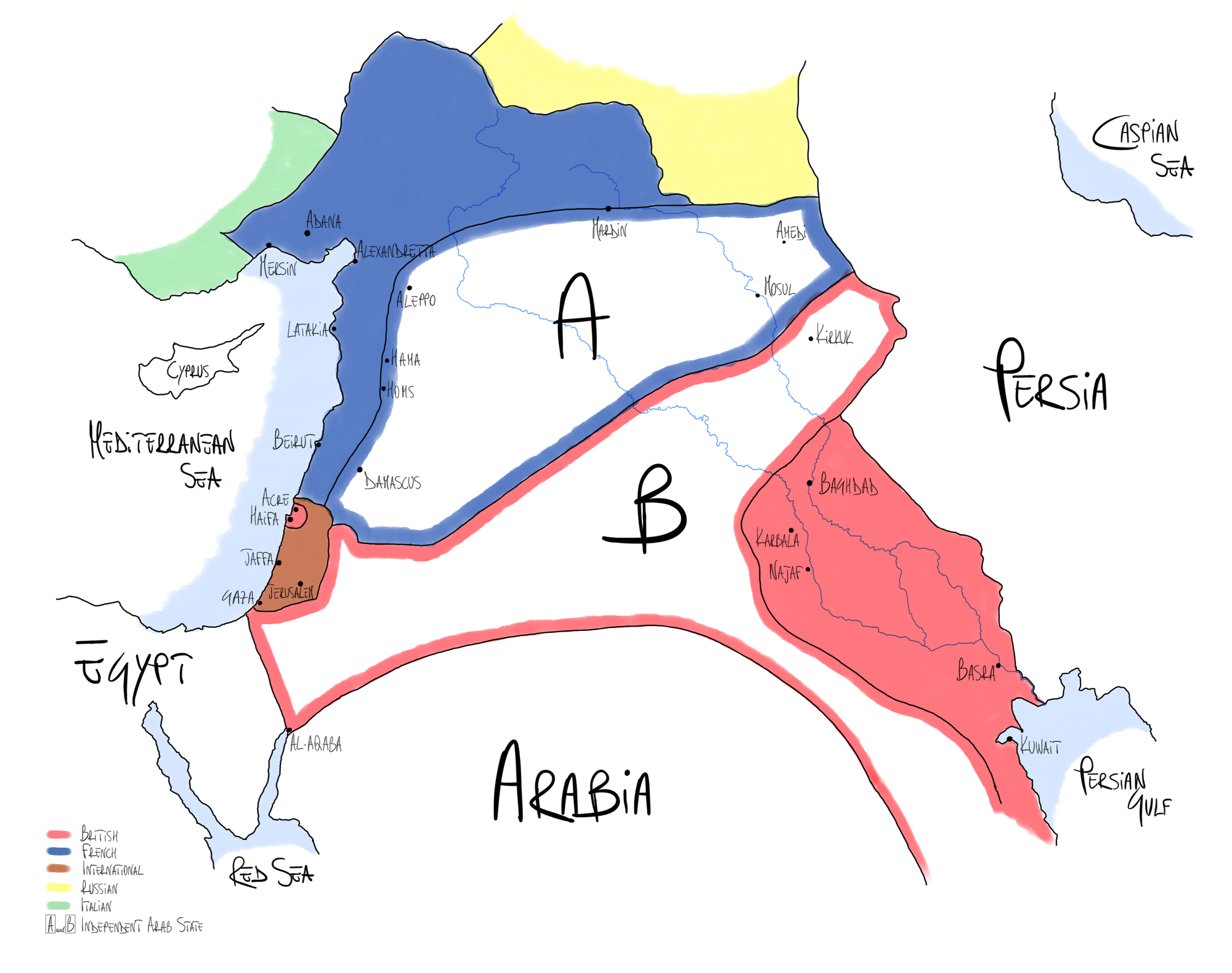

Under this agreement, the Ottoman territories were partitioned into:

- Zones of Indirect Influence (A and B) - indirectly controlled regions earmarked for the establishment of semi-independent Arab states:

“France and Great Britain are prepared to recognize and protect an independent Arab State or a Confederation of Arab States in the areas (A) and (B) marked on the annexed map, under the suzerainty of an Arab chief. That in area (A) France, and area (B) Great Britain, shall have priority of right of enterprise and local loans. That in area (A) France, and in area (B) Great Britain, shall alone supply advisers or foreign functionaries at the request of the Arab State or Confederation of Arab States” (Sykes-Picot Agreement, 1916). (Map 3)

- Zones of direct influence (red and blue):

“In the blue area France, and the red area Great Britain, shall be allowed to establish such direct or indirect administration or control as they desire and as they may think fit to arrange with the Arab State or Confederation of Arab States”. (Map 3)

- Additionally, an International Administration was proposed for the Palestinian territory, excluding the Negev region and the ports of Haifa and Acre, to be accorded to Great Britain:

“In the brown area there shall be established in an international administration, the form of which is to be decided upon after consultation with Russia, and subsequently in consultation with the other Allies, and the representatives of the Shereef of Mecca”. (Map 3)

This would have allowed the British to create a belt between their possessions in Egypt and Iraq.

2.3. The Balfour Declaration

British efforts to win the war and influence the post-war landscape led them to side with the Zionist movement which aimed to establish a Jewish state in the Palestinian region.

Several draft declarations were created in support of the Zionist cause, and the ultimate version was deliberately toned down and made ambiguous (Bickerton & Klausner, 2016, Ch.2).

The British government thus formalised support for such a cause through the Balfour Declaration in 1917:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country”.

- On the one hand, the wording “in Palestine”, without specifying borders, is vague enough to allow for an interpretation whereby such a state does not extend over the whole region but over a part of it.

- On the other hand, the phraseology “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities” intentionally leaves their political and national economic rights to be defined at a later stage.

3. The Mandate System

Following the conclusion of the war, the allocation of territories began.

The official declaration of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points in 1918 played a crucial role, placing a strong emphasis on the principle of self-determination of peoples and thus significantly shaping the partition process.

“Woodrow Wilson had consistently opposed the annexation of land as spoils of war” and supported the creation of the League of Nations to manage the allocation process (Smith, 2017, Ch.2).

Accordingly, the Covenant (1919) of the newborn League of Nations, aimed to incorporate the concept of self-determination to shape future territorial partitions.

Specifically, Covenant Article 22 outlined a Mandate System designed to regulate the administration of territories “which as a consequence of the late war have ceased to be under the sovereignty of the States which formerly governed them” (Covenant of the League of Nations, 1920).

- The communities were categorised into 3 classes (A, B, C) according to “the stage of the development of the people, the geographical situation of the territory, its economic conditions and other similar circumstances”.

- Certain communities belonging to the former Turkish empire, including Palestine, fell into Class A, the class of the most advanced countries and thus with greater independence from colonial powers since they “have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone”.

- The purpose of the Mandate was to “encourage the development of political, economic, and social institutions to the point that self-government would result and that the mandatory power would withdraw” (Smith, 2017, Ch.2).

4. The Mandate for Palestine

The distribution of the Mandates took place through

- the San Remo conference, leading to

- the first Mandate for Palestine, which was later amended through

- the Transjordan Memorandum, resulting in the final version of the Palestinian Mandate.

4.1. The San Remo Conference

The allocation of Mandates occurred during the San Remo Conference on April 25, 1920, where it was collectively agreed that:

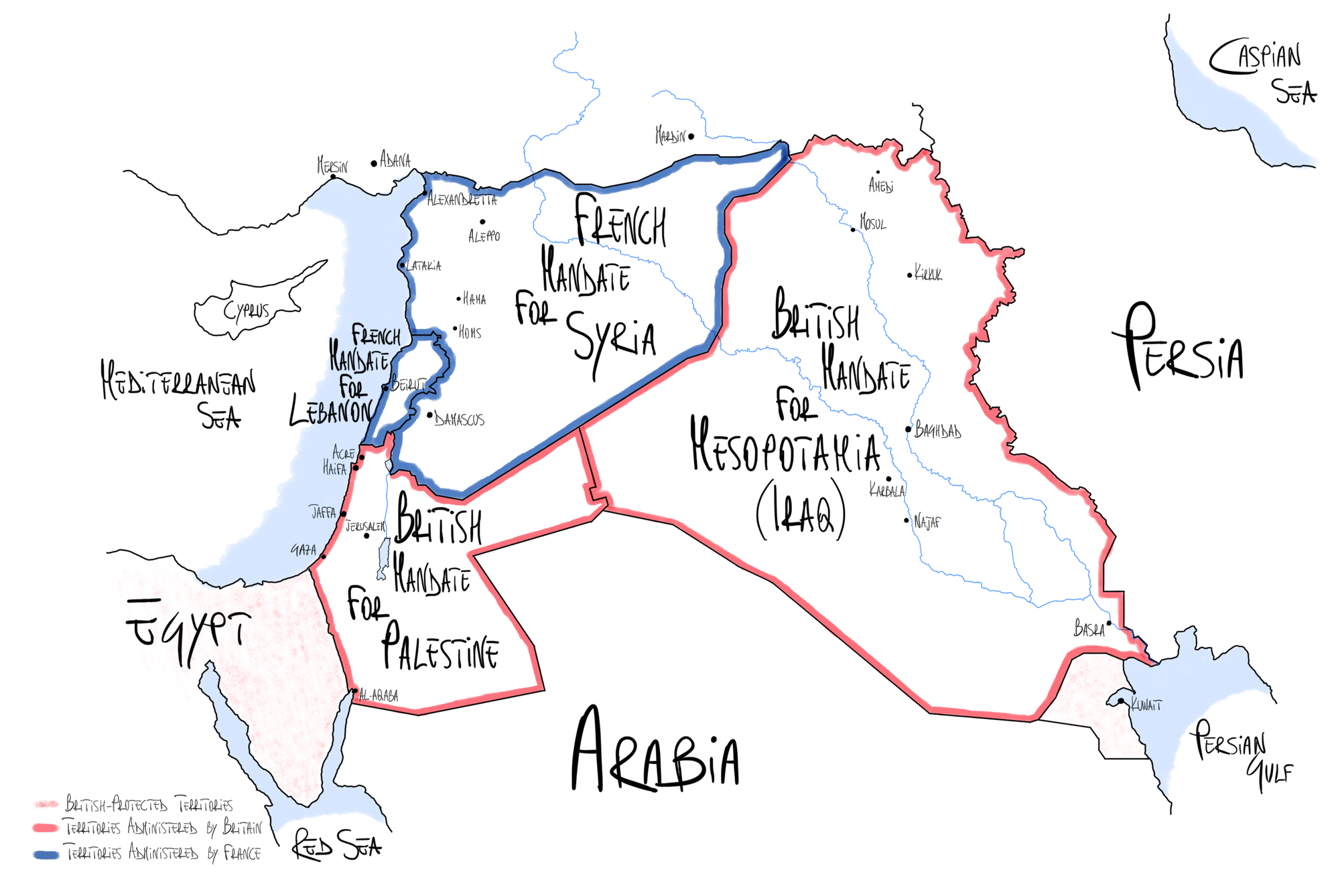

“Les mandataires choisis par les principales Puissances alliées sont : la France pour la Syrie, et la Grande-Bretagne pour la Mésopotamie et la Palestine” (British Secretary, 1920, p.928).

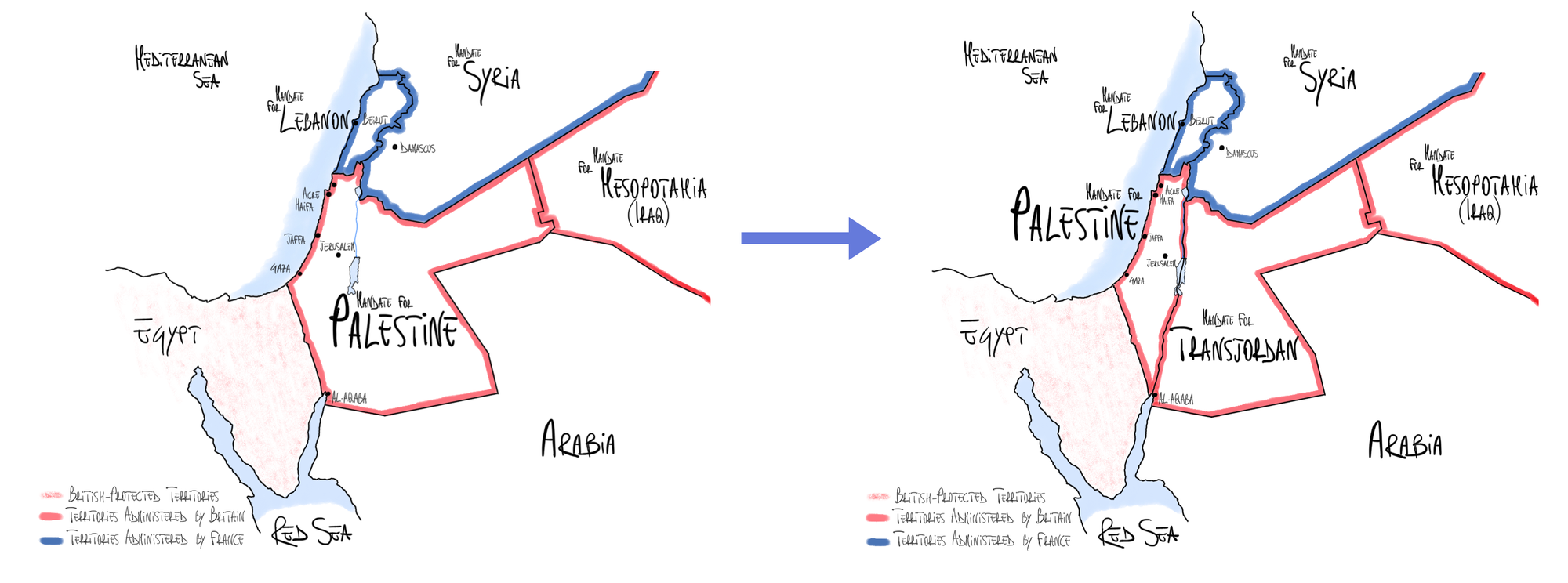

Therefore, France took the Mandate over Syria (today’s Lebanon and Syria) and Great Britain over Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) and Palestine (today’s State of Israel, State of Palestine and Jordan) (Map 4).

4.2. The Mandate for Palestine and the Early Shape of Palestine

Precise borders were identified for the first time for the region of Palestine: this included both the territories West of the Jordan River and those to the East up to the Iraqi border.

As a matter of fact, the first version of the Mandate for Palestine, approved by the Council of the League of Nations on 24 July 1922, made no distinction between the East and West Banks, the whole region being identified as Palestine. (Map 4)

The Mandate, “giving effect to the provisions of Article 22 of the Convenant of the League of Nations”, identified the British government as “Mandatory [...] on behalf of the League of Nations”, being

“responsible for placing the country under such political; administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home […] and the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion” (League of Nations. Council, & UN. Secretary-General, 1947, Art.2).

Therefore, the decision was made to incorporate the Balfour Declaration of November 2, 1917, into the Mandate for Palestine, instructing Britain to lead the country toward the establishment of an independent Jewish state.

The Mandate was equally clear in establishing that

“No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief” (Art.15).

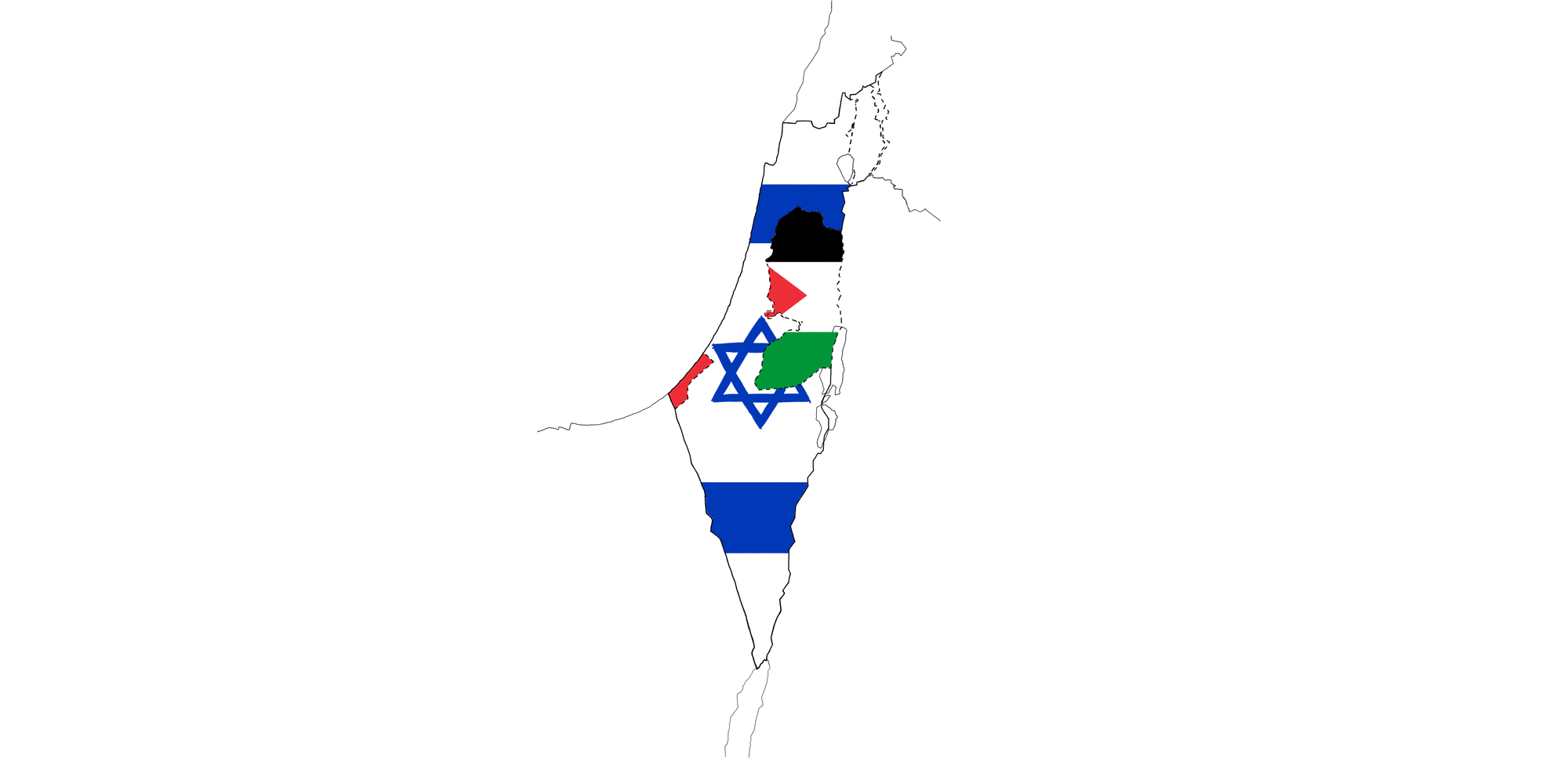

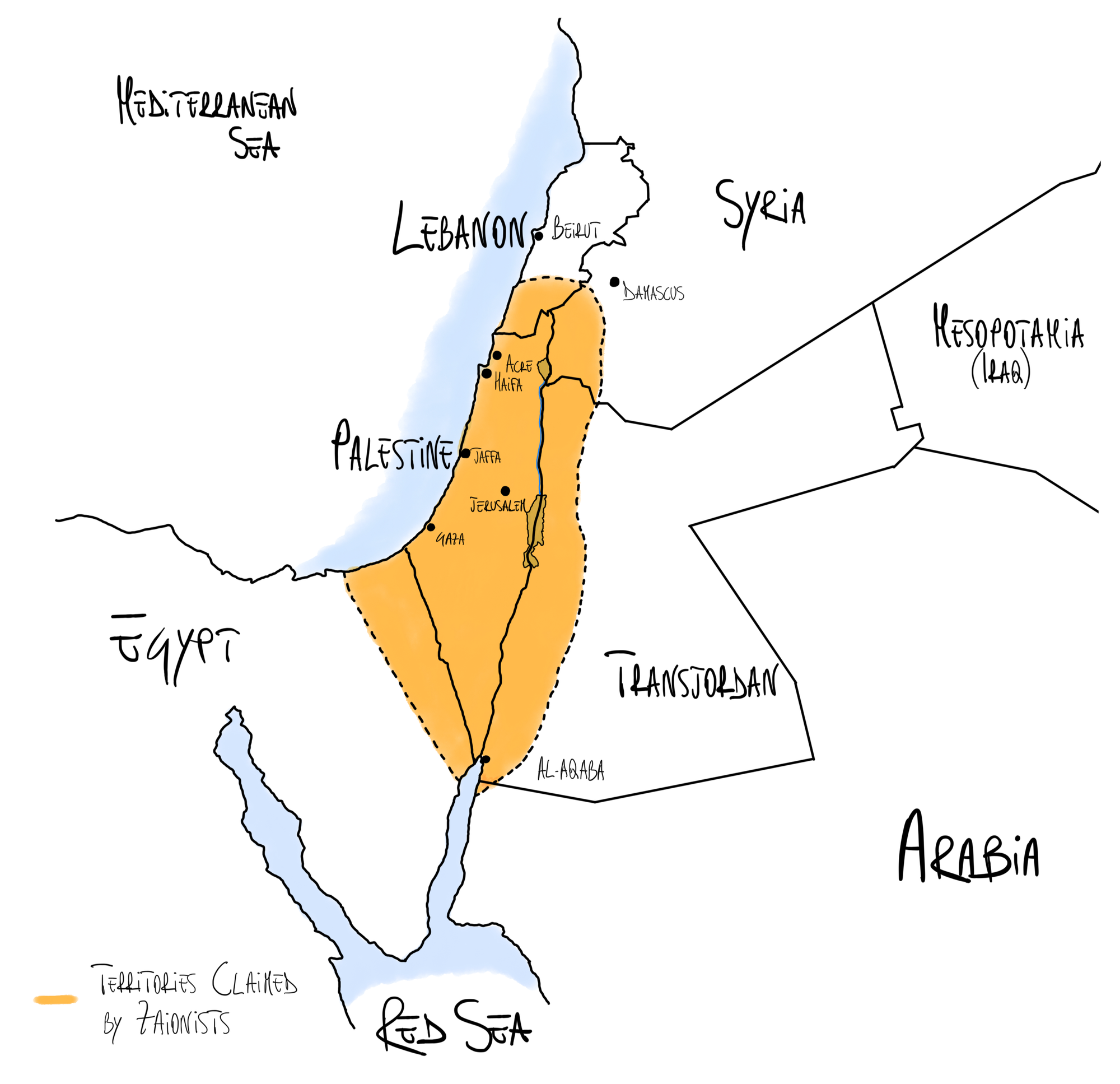

Lands Claimed by Zionists ➡️

4.3. The Transjordan Memorandum and Modern-day Palestine

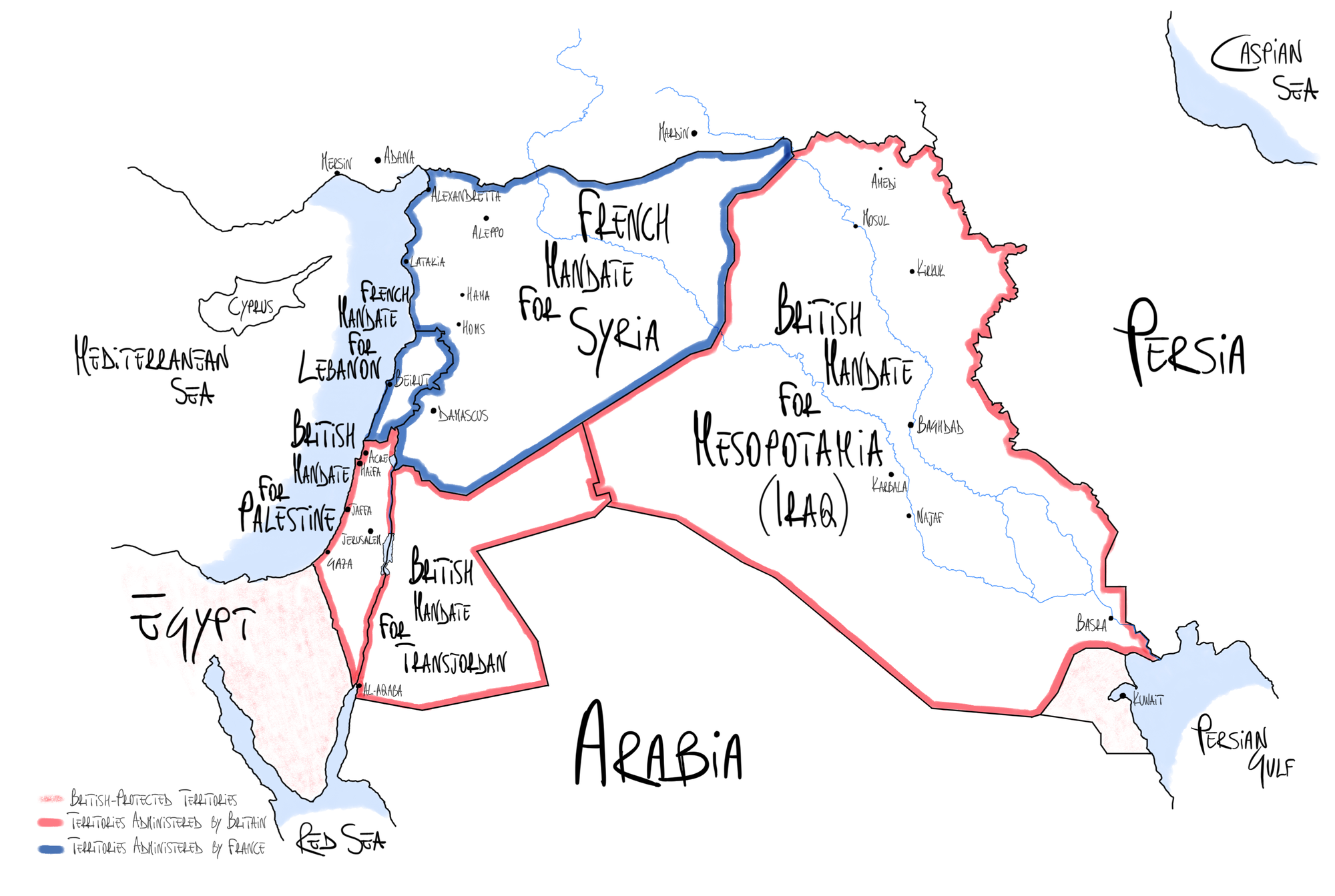

It was only in September 1922 that the British government amended the Mandate through the Transjordan Memorandum, narrowing down what was meant by Palestine.

Article 25 of the new Mandate stated that:

“In the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined, the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this Mandate” (League of Nations. Council, & UN. Secretary-General, 1947). (Map 6)

This is where the contemporary conception of the Palestinian region took shape.

- The area situated to the West of the Jordan River, referred to as Cisjordan or West Bank (from Latin Cis-Jordan, meaning on this side of the Jordan River), was designated as Palestine, intended to be the birthplace of the new Jewish state.

- Conversely, the region East of the Jordan River, known as Transjordan (from Trans-Jordan, meaning over the Jordan River), was intended to be retained by Arab authorities, featuring an independent administration under British supervision, “in the application of the [new] Mandate to Transjordan” (League of Nations. Council. & UN. Secretary-General, 1947).

5. Palestinian Population

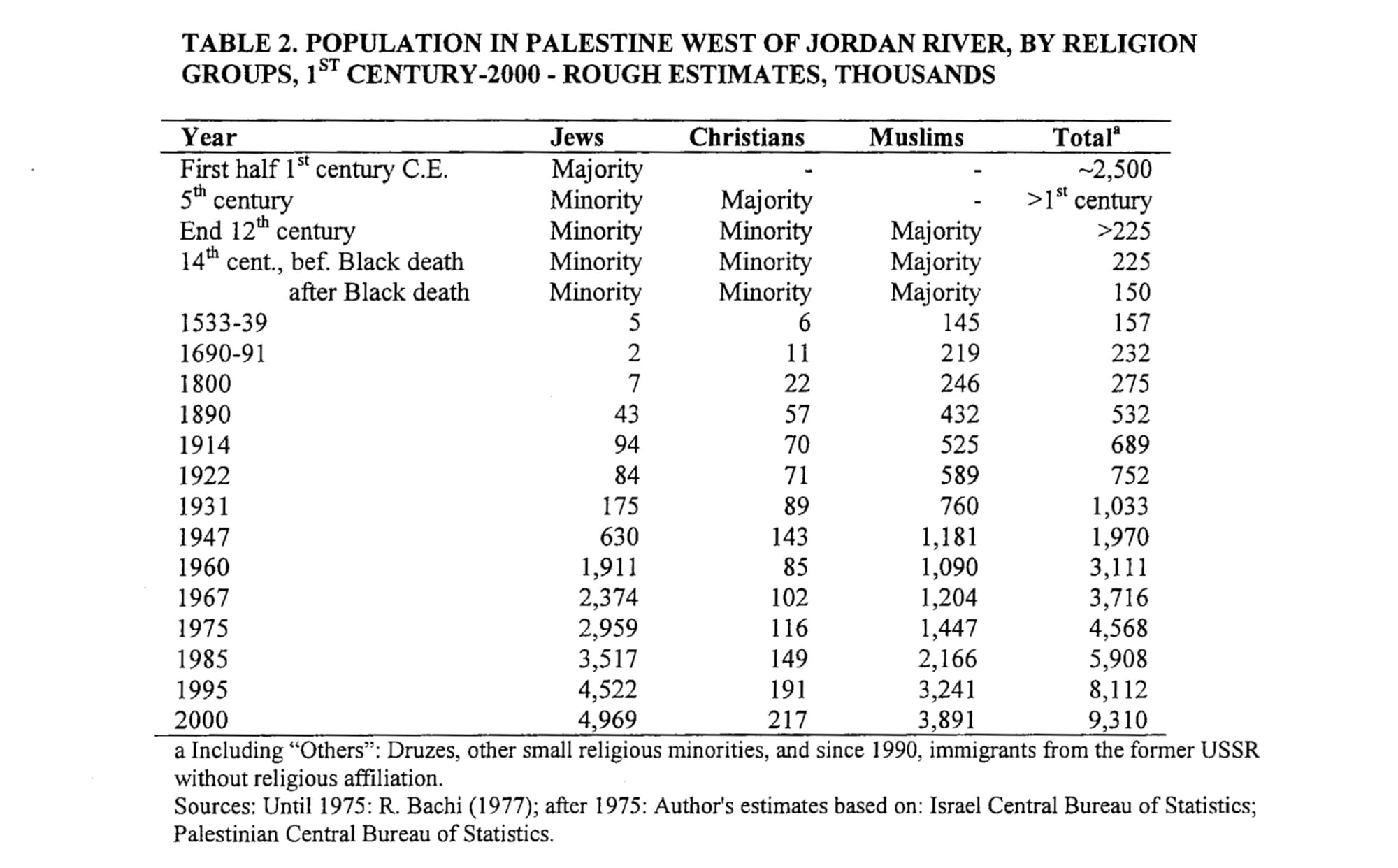

The Arab population of the region in the late 19th century is estimated to be around 450,000.

This number would later increase to 550,000 at the outbreak of the First World War. On the other hand, the Jewish population in 1914 numbered between 60,000 and 90,000 (data based on multiple texts to provide an unbiased estimate of the population: Bickerton & Klausner, 2016, Ch.1; Smith, 2017, Ch.1; Della Pergola, 2001, p.5).

The Jewish population thus accounted for 10% of the total Palestinian population. This made it the “higher proportion of Jews than in any other country, and in some major centers, like Jerusalem, they represented a majority of the population” (Bickerton & Klausner, 2016, Ch.1).

It should be noted here that Palestinians are then both Arabs and Jews who live in the region of Palestine, also referred to as the Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael) by Jews.

As Golda Meir, Israel’s Prime Minister from 1969 to 1974, said in an interview with ThamesTv in 1970:

“What difference is there between Arabs who were on this side of the Jordan and the other side of the Jordan? Arabs in the East Bank and […] the West Bank. When were Palestinians born? What was all this area before World War I? When Britain got the mandate over Palestine, what was Palestine then? Palestine was then the area between the Mediterranean and the Iraqian border”.

“You say there is no such thing as Palestinians?” - Interviewer.

“No, East and West Bank was Palestine. I am a Palestinian. From 1921 until 1948 I carried a Palestinian passport. There was no such thing in this area as Jews, and Arabs, and Palestinians. There were Jews and Arabs. […] I don’t say there are no Palestinians. But I say there is no such thing as a distinct Palestinian people of all the Palestinians who live in Jordan. Why have the Palestinians in the West Bank become more Palestinians […] than they were before?” (ThamesTv, 2014).

📌 Conclusions

- A shift occurred following WWI and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire when, in 1922, the League of Nations identified Palestine as the territory where a state for the Jewish people was to be established, entrusting the British with the responsibility of implementing this decision.

- As a result of this resolution:

- Palestine, in its contemporary conformation and conception, was thus born out of the institution of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1922.

- Palestine as a united political entity never existed until the British Mandate.

References 📃

- Balfour, A. (1917). Balfour Declaration.

- Bickerton, I. J., & Klausner, C. L. (2016). A history of the Arab-Israeli conflict (Seventh edition). Routledge.

- Biger, G. (2008). The Boundaries of Israel—Palestine Past, Present, and Future: A Critical Geographical View. Israel Studies, 13(1), 68–93. JSTOR.

- British Secretary, (1920) Minutes of Palestine meeting of the Supreme Council of the Allied Powers held in San Remo at the Villa Devachan April 24 1920. Jewish Virtual Library.

- Churchill, W. (1922) "British White Paper of June 1922." Yale University, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/brwh1922.asp

- Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, G.C.M.G., His Majesty's High Commissioner at Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca July, 1915-March, 1916, [Cmd. 5957], House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online (1939). London.

- Covenant of the League of Nations. February 1920. League of Nations.

- Della Pergola, S. (2001). Demography in Israel/Palestine: Trends, prospects, policy implications. Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry.

- League of Nations. Council, & UN. Secretary-General. Text of Mandate [for Palestine]: Note / by the Secretary-General. 13 p. A/292 (18 April 1947) http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/829707

- Lewis, B. (1980). Palestine: On the History and Geography of a Name. The International History Review, 2(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.1980.9640202

- Pappé, I. (2006). A history of modern Palestine: One land, two peoples (2. ed., reprinted). Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Secretary of State for the Colonies. (1939). McMahon-Husain correspondence - Report of Arab-UK committee - UK documentation Cmd. 5974/Non-UN document (excerpts). Question of Palestine. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-199699/

- Smith, C. D. (2017). Palestine and the Arab-Israeli conflict: A history with documents (Ninth edition). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Sykes-Picot Agreement. United Kingdom-France. May 1916.

- ThamesTv. (2014, August 5). Israel | Golda Meir interview | Prime Minister interview [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w3FGvAMvYpc

- United Nations. (1978). The origins and evolution of the Palestine problem. Part 1, 1917-1947. United Nations Digital Library System.