Decoding Deterrence: the Essentials of the Art of Persuasion

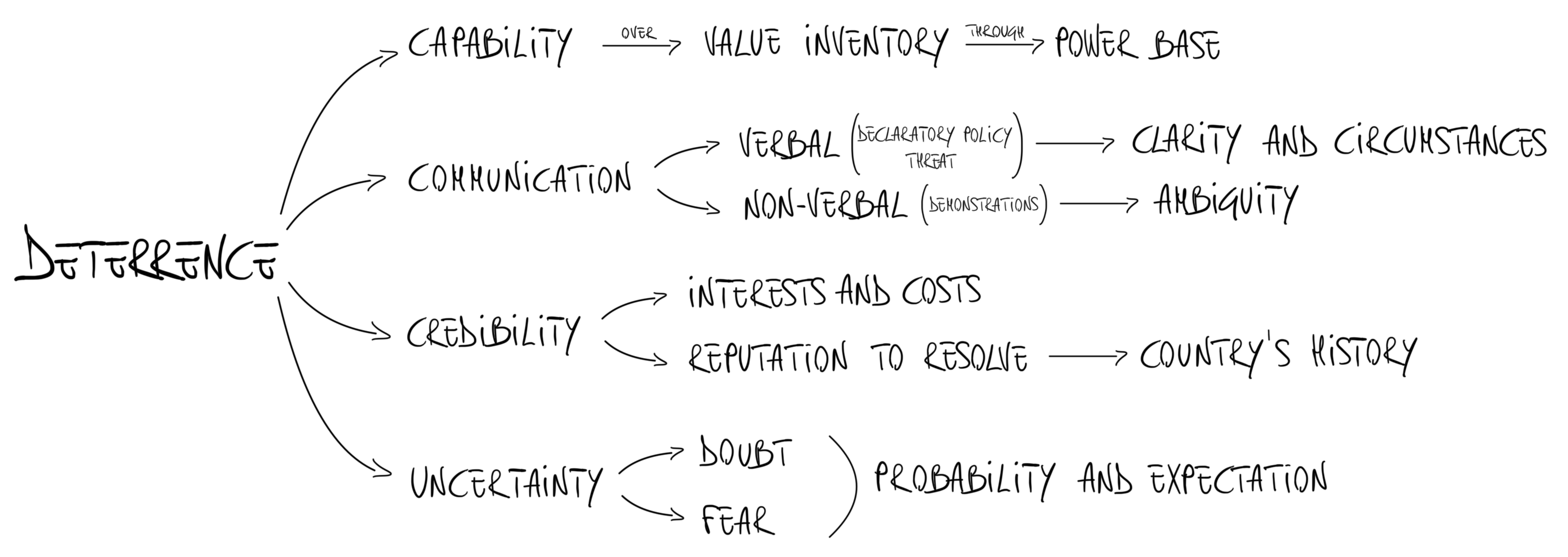

Deterrence Persuasion is an intricate interplay between Capability, Communication and Credibility. Their thoughtful combination together with a dose of Uncertainty shapes the delicate balance between Peace and Conflict.

Decoding Deterrence: the Essentials of the Art of Persuasion

In an interview conducted by the Strategic Studies Quarterly journal, John Mearsheimer (2018) states that “conventional deterrence is all about persuading an adversary not to initiate a war because the expected costs and risks outweigh the anticipated benefits” (p.3).

To successfully carry out such persuasion, one must bear in mind three fundamental elements of a deterrence strategy: capability, communication, and credibility (Harrison et al., 2017).

In Snyder’s (1961) words

“deterrence may follow, first, from any form of control which one has over an opponent’s present and prospective ‘value inventory’ [Capability]; secondly, from the communication of a credible threat or promise to decrease or increase that inventory [Communication]; and, thirdly, from the opponent’s degree of confidence that one intends to fulfill the threat or promise [Credibility]” (p.10).

A valid deterrence strategy should focus on all three elements.

Nevertheless, it is not necessarily true that a strategy based on two of them will fail.

For instance, a strategy that relies heavily on communication and credibility, although fallacious in the element of actual military capabilities, could prove effective.

In fact, since deterrence acts on the enemy’s psychology, it could still persuade him not to attack by deceptively altering his cost-benefit analysis.

…

In this article, the three fundamental elements of a deterrence strategy, namely

- Capability,

- Communication, and

- Credibility,

are analysed individually. In addition, the choice has been made to include the element of

- Uncertainty

despite the fact that it is often analysed separately.

This is because, although one may not have as much control over it as over the other three elements, it is a tool that is still possible to use to one’s advantage, and it will be explained why and how.

1. Capability

The first element mentioned by Glenn Snyder (1961) is the capability, defined as

“Any form of control which one has over an opponent’s present and prospective ‘value inventory’” (p.10).

He also refers to the value inventory as object values defining it as

“The values of the other party, which are subject to being decreased or increased by the actual carrying-out of the threat or promise” (Snyder, 1960, p.164).

Therefore, in the assessment of potential costs, the enemy must consider the damage or loss of such values.

In order to establish the capabilities that can harm the value inventory, one must first understand what these values could be.

Value inventory (Object Values)

The value inventory is divided into intrinsic value or power value:

- Intrinsic values, also called end values, are those values whose importance lies in their own right.

- These could be values such as our independence, or even the independence of countries we are extremely close to, or share the culture of. For the United States, for example, an intrinsic value could be the independence of EU countries, and vice versa.

- To continue with intangible values, they can be “moral values such as self-respect, honor, and prestige” (Snyder, 1961, pp.31-40).

- On the other hand, intrinsic tangible values can be material assets and human lives.

- Power values, on the other hand, can also be called instrumental values, as they are not important per se, but are of relevance as they are instrumental to the safety and security of the intrinsic values (Snyder, 1961, pp.31-40).

- Sometimes, they can coincide with the intrinsic values, as is the case with the raw materials of the land or military forces:

- important insofar as they are necessary for national security and thus to maintain independence

- but also as such, as national territory and human lives.

A comprehensive definition refers to the “assets at stake” during an international conflict: these assets “are valued on two scales—a power scale and an intrinsic scale—and that the aggregate value of any given asset is the sum of its valuation on both scales” (Snyder, 1961, pp.31-40).

Lastly, the value inventory, depending on its purpose, can be of strategic, deterrent, or political value (Snyder, 1961, pp.31-40).

Now that the value inventory has been defined, it can be well understood that capabilities can be not only military but also economic and influential.

An all-encompassing definition of capability is provided by the same Snyder as

“The capacity to affect object values by application of a power base” (Snyder, 1960, p.165).

- Power can be identified in four components: (1) the base of power, (2) the means or instruments to exercise it, (3) the amount or extent of power and (4) its purpose (Dahl, 2007).

- The base of power (or power base) that an actor can use “consists of all the resources - opportunities, acts, objects, etc. - that he can exploit in order to effect the behavior of another” (Dahl, 2007, p.203). It could thus be veto power in an international organisation or influence over third countries.

- The capability may then consist of non-military means as well as military means. We could then threaten to apply sanctions or trade restrictions as well as bomb all major cities.

Finally, for clarification purposes, the literature sometimes refers to the capability to describe the effectiveness of the threat. In this case, the threat is considered capable if “and only if the threatened player prefers the Status Quo to Conflict; when this relationship is reversed, the threat will be said to lack capability” (Zagare & Kilgour, 2000). In this research, this second meaning of the term will be left aside.

2. Communication

A good deterrence strategy, in addition to having demonstrated capabilities, must also have express intentions regarding its purpose (Kaufmann, 1989). This requires good communication.

Taking up again Snyder’s (1961) definition of deterrence, “deterrence may follow […] secondly, from the communication of a credible threat or promise to decrease or increase that inventory” (p.10).

- In fact, an actor may be able to inflict damage on the enemy if attacked, but without effective communication, this would be useless for deterrence.

- Here, deterrence would fail since the enemy would not perceive the danger arising from the threat.

- Hence “for a threat to be an effective deterrent, it must be clearly communicated, and the outcome demanded be plainly specified” (Langeland & Grossman, 2021, p.8).

When planning a deterrence strategy, it is necessary to decide how to communicate one’s intentions and capabilities to the enemy. Communication can be handled verbally and non-verbally. Hence, there are two different types of communication strategies: one based on statements, and one based on demonstrations.

2.1. Verbal Communication: Statements

Declaratory policy is a communication strategy relying solely on verbal or written statements (Snyder, 1961, pp.239-252).

The importance of an effective declaratory policy is stressed by the existence of psychological pressure, cognitive limitations and cognitive biases that plague human beings when confronted with difficult decisions (Jervis, 1989).

- Jervis (1989) identifies these communication challenges:

- Understanding: during interactions between international actors, it is often the case that they do not understand each other’s goals, perceptions, and fears;

- Misinterpretations: signals and commitment warnings are often misinterpreted or misperceived;

- Misestimates: human beings tend to underestimate or overestimate according to their convenience;

- Timing: due to the difficulty of discerning the adversary’s goals and perceptions, it is complicated for the deterrer to find the right timing for its communication.

The forms a declaratory policy can take are virtually infinite, ranging from public speeches by government officials, press conferences, official documents adopted by parliaments or governments, resolutions, and budget notes to the most solemn and powerful form: treaties.

Whatever form it takes, the most important declaratory policy is the threat.

The Threat

The communication of a threat by the deterrer must contain two fundamental components:

- “a contingency or enemy move which will bring about a certain sanction or response; [the threshold]

- and […] an indication of the consequences or costs which the enemy must expect as a result of his move [the description of the response]”, whatever form it takes, from sanction to punishment (Snyder, 1961, p.241).

The threat, once issued, creates a commitment, based on values such as honour, prestige and future credibility, to its fulfilment; a commitment that did not exist before and which entails a cost.

However, some threats do not bring about this commitment: these are termed bluffs. However, even these threats entail a “cost in non-fulfillment, but not enough to create a balance of gain over cost in actually carrying out the threats”(Snyder, 1961, p.242). The success of this strategy lies in the lack of complete information regarding the cost-benefit calculus of the deterrer by the enemy.

Clarity of the Threat Statement

The threat statement may vary in the clarity of the information provided.

- Normally, the greater the clarity, the better the threat (Snyder, 1961, pp.239-252). Nevertheless, there are several reasons why excessive clarity could be counterproductive to deterrence:

- First, going into too much detail about the actions that will be taken should one be attacked, would allow the enemy to prepare for such actions in order to minimise its cost.

- Second, if the situation that would lead to the retaliatory action of the deterrer (the threshold) is described too accurately, the enemy could launch the attack in such a way as not to fulfil these conditions and in so doing, fail to meet the deterrence.

- Third, paradoxically, a declaration of a precise sanction or action would result and be perceived as a declaration of non-commitment to more severe measures.

- On the other hand, there could be several benefits that an ambiguous statement could bring.

- Although ambiguity generally reduces the effectiveness of deterrence, it could also reduce the cost of its failure. By remaining ambiguous about the qualities of the deterrence measures, the deterrer could easily renege on his commitment, minimising the cost he would have paid in the form of prestige, credibility, and honour (Snyder, 1961, pp.239-252).

- A certain degree of ambiguity could enhance deterrence, creating doubt and anxiety in the enemy about the actual deterrent measures. As a matter of fact, there are many speeches by government officials in which one hears the expression “there will be severe consequences” or “we will not stand still”, yet with no clear indication of what these consequences will entail.

Circumstances of the Statement

If the threat simply takes the form of the ambiguous one above, it will probably have little credibility.

However, threats made through a declaration to a public audience are much more effective than confidential ones (Snyder, 1961, pp.239-252). This is because a public announcement of a threat commits not only the credibility and prestige of the entire nation in carrying it out but also that of its author vis-a-vis his people. Threats made secretly, in a private context, allow the author not to lose face should this be later disregarded.

Furthermore, the more formal the context in which the declaration is made, the more solemn the threat will be and thus the more credible it will be for deterrence purposes (Snyder, 1961, pp.239-252).

The same logic follows the difference between an oral threat and a written one, the latter being more authentic and binding than the former.

Finally, it must be pointed out that excessive repetition of a threat could weaken the threat itself, due to the so-called threat inflation phenomenon (Snyder, 1961, p.249).

2.2. Non-Verbal Communication: Demonstrations

Non-verbal communication makes open use of actions, often expressed in force demonstrations, for the purposes of deterrence.

Demonstrations of force for communication purposes can take the most diverse forms, ranging from the conduct of manoeuvres near borders – as was the case between Russia and Ukraine in 2021 –, to naval exercises near adversary territorial waters, or even the recall of discharged military personnel.

These strategies are often combined with verbal communication strategies to reinforce them. Military forces could be mobilised, by means of preparatory moves, in such a way as to prepare for the fulfilment of the threat made verbally.

Nevertheless, their inherent degree of ambiguity makes them extremely flexible, allowing their author to justify such actions as routine. Furthermore, demonstrations of force allow the deterrer to threaten an enemy without specifying exactly how much force will be used should he be attacked (Snyder, 1961, pp.239-252).

Despite all the listed benefits of force demonstrations, they bring with them dangers. Indeed, by mobilising forces at the borders and carrying out military exercises, mishaps could occur that would lead the deterrer towards the destiny it was intended to avert: war.

Despite this danger, the unscrupulousness of the deterrer could play on the enemy’s concern of such incidents occurring, to make him back down in fear of a war for which he is not yet ready at that moment.

Every sort of communication must be carefully performed.

Getting out of hand by bringing into play the honour and prestige of the enemy one wishes to deter, for example by flaunting one’s moral superiority, could have anti-deterrent effects, bringing the time of war one step closer.

This occurs when “people (and nations) do not like to ‘back down’ before a threat made by an opponent who is presumed to be their juridical, social, or organizational ‘equal’” (Snyder, 1961, p.245).

3. Credibility

When it comes to deterrence, whether it is carried out by means of a threat or denial, “we often forget that both sides of the choice, the threatened penalty and the proffered avoidance […] need to be credible” (Schelling, 2008, p.75).

The issue of credibility is a key point when dealing with the theory of deterrence.

The question of whether the deterrent threat is credible or not makes all the difference: “Credibility and clear communication demonstrating the will and ability to use capabilities is essential” (Ducheine & Pijpers, 2021).

Its role is so essential that Freedman (2003) goes so far as to describe it as a magic ingredient (p.96).

Credibility is defined by Glenn Snyder (1960) as

“The perception by the threatened party of the degree of probability that the power-wielder will actually carry out the threat if its terms are not complied with or will keep a promise if its conditions are met” (p.164).

In easier words, it is “the extent to which a threatener is seen to prefer to execute the threat” (Zagare & Kilgour, 2000, p.67).

For the threat to work as a deterrent, it must be accompanied by an effective will to proceed, or at least that this appears to be real. If the will is not there, and the enemy is aware of this, the strategy fails because the threat is not credible. For Example:

- Should a European state threaten another that, in the event of an attack, it would bomb the enemy’s hospitals, this threat would not be credible either because the European state would not actually be willing to bomb the hospitals as it would be considered a war crime, or because the population would support such a choice. In any case, the threat would not be credible.

- A further possible case could be when an actor were to threaten to use his veto power in an international forum. Yet, if the enemy were to possess some power to retaliate against the threatening actor, such as by blackmailing him privately, he would be sure that the threat would not be carried out. Again, in the enemy’s eyes, the deterrent would not be credible.

An interesting case is when the threat issued by the deterrer, should it actually be carried out, would result in enormous damage that would also backfire on the deterrer itself. In this case, too, the threat would lack credibility. The case in question is that of nuclear massive retaliation. In such a case, the lack of credibility could be overcome with a limited retaliation strategy.

It can therefore be argued that credibility depends mainly on two factors:

- the interest and cost

- and the reputation of resolve

of the deterrer perceived by the attacker (Kertzer, 2016).

In fact, “an actor that is able to credibly signal its resolve — usually by taking risks that an irresolute actor would be unwilling to tolerate — will successfully avert war on its desired terms” (Kertzer, 2016, p.8).

The problem of credibility plagues many international actors as “credibility is not an objective, nor is it a property of the person or state making the threat. Rather it is ‘owned’ by the target” (Jervis, 2016, p.68).

After all, credibility also derives from a country’s history and its behaviour over time. If a country is known to lie and threaten out of hand, without actually ever having carried out what it declared, it is unlikely to be believed by others when it is actually serious. Credibility therefore seems almost a trait that is earned over time.

From the enemy’s point of view, the credibility of the deterrer results from “an assessment about the likelihood that a deterrer will respond to a specific action by a specific party in a specific way at a specific time” (Harrison et al., 2017, p.22).

Hence, much seems to depend on “how observers assess evidence and on what evidence they decide to assess” (Yarhi-Milo, 2013, p.46).

- As Jervis (2016, p.67) reports, in 1969 the United States launched a nuclear alert to impress the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The USSR, however, did not notice. In this case, not only was the nuclear alert not entirely credible, but the threat was not even alerted by the enemy and no deterrence evidence was assessed. Consequently, the US action failed in its scope.

This event introduces the next element and its crucial relevance: uncertainty.

4. Uncertainty

“Uncertainty is a synonym for life, and nowhere is uncertainty greater than in international politics” (Waltz, 1993, p.60).

As early as the beginning of the 19th century, when addressing the subject of war, Clausewitz (1832/2007) had already emphasised the centrality of this element.

“The art of war deals with living and with moral forces. Consequently, it cannot attain the absolute, or certainty; it must always leave a margin for uncertainty” (p.46).

Just like war, deterrence is an interaction between two actors, and since “most, if not all, interstate relationships are characterized by, among other things, nuance, ambiguity, equivocation, duplicity, and ultimately, uncertainty”, it is thus not exempt from the element of uncertainty (Zagare & Kilgour, 2000, p.104).

Actually, one could go so far as to claim that uncertainty is not merely an element of deterrence, it is indeed “the very linchpin of the system of deterrence” (Tunander, 1989, p.355).

“Deterrence cannot possibly succeed unless there is some degree of uncertainty in the mind of the would-be attacker” (Huth & Russett, 1990).

If the deterrent threat does not instil in the attacker’s mind the doubt, the fear, the uncertainty about what might happen if he attacks, then deterrence may not be effective.

Therefore, uncertainty itself acts as a deterrent factor: as the level of uncertainty increases, the aggressor becomes less confident about the possible outcome of a clash with the enemy (Huth et al., 1992). On the contrary, as uncertainty decreases, confidence increases.

Robert Jervis argues that “certainty as to whether an adversary will stand firm is rare. Statesmen have to deal with probabilities” (Zagare & Kilgour, 2000, p.99).

Threats, as previously discussed, are not always reliable; they could be uttered purely for deterrence purposes, and thus be bluffs, or they could simply be vague. In both cases, uncertainty is rampant.

When facing such a scenario, the aggressor must deal with probability, yet fortunately, he is not blind.

He can rely on the past actions of the deterrent, on the mobilisation of forces serving the threat’s objectives, and on the manner of diffusion and communication of the threat, which for instance being public and solemn would be more binding, to assign a probability to the events (Snyder, 1960).

Going back to the definition of deterrence as “a function of the total cost-gain expectations of the party to be deterred” the element of uncertainty is inherent in the adjective expectation (Snyder, 1960, p.166).

The attacker faces uncertainty regarding two types of expectations of the deterrer’s payoffs: first, the “in his estimate of the opponent’s estimate of the consequences of his response and, second, in his estimate of the opponent’s valuation of the consequences” (Snyder, 1961, p.28).

After an analysis of the evidence at his disposal and an evaluation of the probabilities, he will choose the most plausible option for making his decisions.

Due to uncertainty, the success of the strategy and the outbreak of war with uncertain outcomes are possible and impossible at the same time and “since it is the aggressor who takes the initiative, it is he who must bear most of the burden of weighing the uncertainties” (Snyder, 1960, p.177).

📌 Key Takeaways

The Essentials of the Art of Persuasion are Capability, Communication, Credibility, and the often-overlooked factor of Uncertainty.

- Capability is any form of control which one has over an opponent’s ‘value inventory’ - comprising both intrinsic and instrumental values - by application of a power base, entangling military, economic, and influential means.

- Communication of a credible threat is crucial since deterrence strategies stand on perceptions. Verbal communication, through declaratory policies and threat statements, is marked by clarity, timing, and circumstances. Non-verbal communication, in the form of force demonstrations, is denoted by its degree of ambiguity and involves taking the risks arising from it.

- Credibility is the perceived willingness and ability of the threatener to carry out threats. It depends on the deterrer’s interest, cost, and reputation of resolve perceived by the attacker. Lack of credibility arises when the threat is unrealistic, inconsistent with values, or the deterrer lacks the will to execute it.

- Uncertainty is considered the linchpin of deterrence, making it essential for success. Deterrence relies on instilling doubt and fear in the potential aggressor’s mind about the outcome of an attack. Unreliable or vague threats contribute to uncertainty; the aggressor must deal with probabilities and past actions to assess the situation.

Crafting a successful deterrence strategy requires the crucial synergy among capability, communication, credibility, and uncertainty. Each element significantly contributes to achieving the desired outcome of dissuading potential adversaries from initiating conflict.

✍️ With a Sketch

References 📃

- Dahl, R. A. (2007). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2(3), 201–215.

- Ducheine, P., & Pijpers, P. (2021). The Missing Component in Deterrence Theory: The Legal Framework. In NL ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2020: Deterrence in the 21st Century—Insights from Theory and Practice (pp. 475–500). TMC Asser Press.

- Freedman, L. (2003). The evolution of nuclear strategy. Springer.

- Harrison, T., Cooper, Z., Johnson, K., & Roberts, T. G. (2017). Escalation and Deterrence in the Second Space Age. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Huth, P., & Russett, B. (1990). Testing Deterrence Theory: Rigor Makes a Difference. World Politics, 42(4), 466–501.

- Huth, P., Bennett, D. S., & Gelpi, C. (1992). System uncertainty, risk propensity, and international conflict among the great powers. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 36(3), 478–517.

- Jervis, R. (1989). Rational Deterrence: Theory and Evidence. World Politics, 41(2), 183–207.

- Jervis, R. (2016). Some Thoughts on Deterrence in the Cyber Era. Journal of Information Warfare, 15(2), 66–73. JSTOR.

- Kaufmann, W. W. (1989). The Requirements of Deterrence. In P. Bobbitt, L. Freedman, & G. F. Treverton (Eds.), US Nuclear Strategy (pp. 168–187). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Kertzer, J. (2016). Resolve in international politics (Vol. 2). Princeton University Press.

- Langeland, K., & Grossman, D. (2021). Tailoring deterrence for China in space. RAND Corporation.

- Mearsheimer, J. J. (2018). Conventional Deterrence: An Interview with John J. Mearsheimer. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 12(4), 3–8.

- Schelling, T. C. (2008). Arms and influence. Yale University Press.

- Snyder, G. H. (1960). Deterrence and power. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 4(2), 163–178.

- Snyder, G. H. (1961). Deterrence and Defense. Princeton University Press. p.10

- Tunander, O. (1989). The Logic of Deterrence. Journal of Peace Research, 26(4), 353–365. JSTOR.

- Von Clausewitz, C. (2007). On War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Waltz, K. N. (1993). The Emerging Structure of International Politics. International Security, 18(2), 44–79. JSTOR.

- Yarhi-Milo, K. (2013). In the Eye of the Beholder: How Leaders and Intelligence Communities Assess the Intentions of Adversaries. International Security, 38(1), 7–51.

- Zagare, F. C., & Kilgour, D. M. (2000). Perfect Deterrence (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.