Israel Security Threat Assessment

Security Threats can be classified on their Nature: Conventional, Non-Conventional, Terrorism. Alternatively, Israeli Military Authorities use a "Circles" system based on proximity to civilian centres, thus distinguishing First-, Second-, Third-Circles threats. What do these classifications entail?

Israel Security Threat Assessment

In 1948, Israel declared its independence from the British Mandate of Palestine according to the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine as Resolution 181 (II) against the will of all its neighbouring states. Consequently, it has consistently confronted significant and widespread opponents and existential threats. Although threats have evolved over time and opponents’ modes of engagement have changed, their numbers have fortunately decreased.

This article aims to outline Israel's main adversaries and threats to its national security.

The analysis proceeds by distinguishing according to the nature of the threat:

- Arab Conventional Military Capabilities (conventional threat),

- Arab and Iranian Non-Conventional Capabilities (non-conventional threat),

- Terrorism and Guerrilla Warfare.

Finally, a classification of these threats used by the Israeli military authorities is presented. The classification is currently based on three “Circles of Threats” according to the proximity of the threat to civilian centres.

1. Arab Conventional Military Capabilities

Considered a conventional threat, the conventional military capabilities of the Arab states' official armies posed the most significant challenges to Israel during its early years of statehood (Kam, 2003, pp.358-359).

Since 1948, when Israel declared its independence from the British Mandate of Palestine according to the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine as Resolution 181 (II) - the so-called Two-state solution -, Israel was confronted against a coalition of Arab states throughout the 3 largest Arab-Israeli wars.

- The 1948 Arab-Israeli War, triggered by Israel's declaration of independence, occurred as neighbouring Arab states, including Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, mobilised their forces to oppose the establishment of the Jewish state, seeking to neutralise it.

- The 1967 Six-Day War started with Israel's pre-emptive attack against Egypt, which had previously declared the closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli vessels, mobilised the Egyptian military along the border, and issued orders for the immediate withdrawal of all United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) deployed since the Suez Crisis to ease tensions (Mutawi, 2002). Israel's rapid victory over the Egypt-Jordan-Syria coalition resulted in the occupation of the West Bank, Golan Heights, Gaza Strip, and Sinai Peninsula.

- The 1973 Yom Kippur War, initiated by surprise attacks from Egypt and Syria on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, challenged Israel's military prowess, resulting in a costly but ultimately successful defence.

Throughout this time, Israeli military leaders categorised potential threats from neighbouring Arab states based on their proximity to Israeli civilian centres.

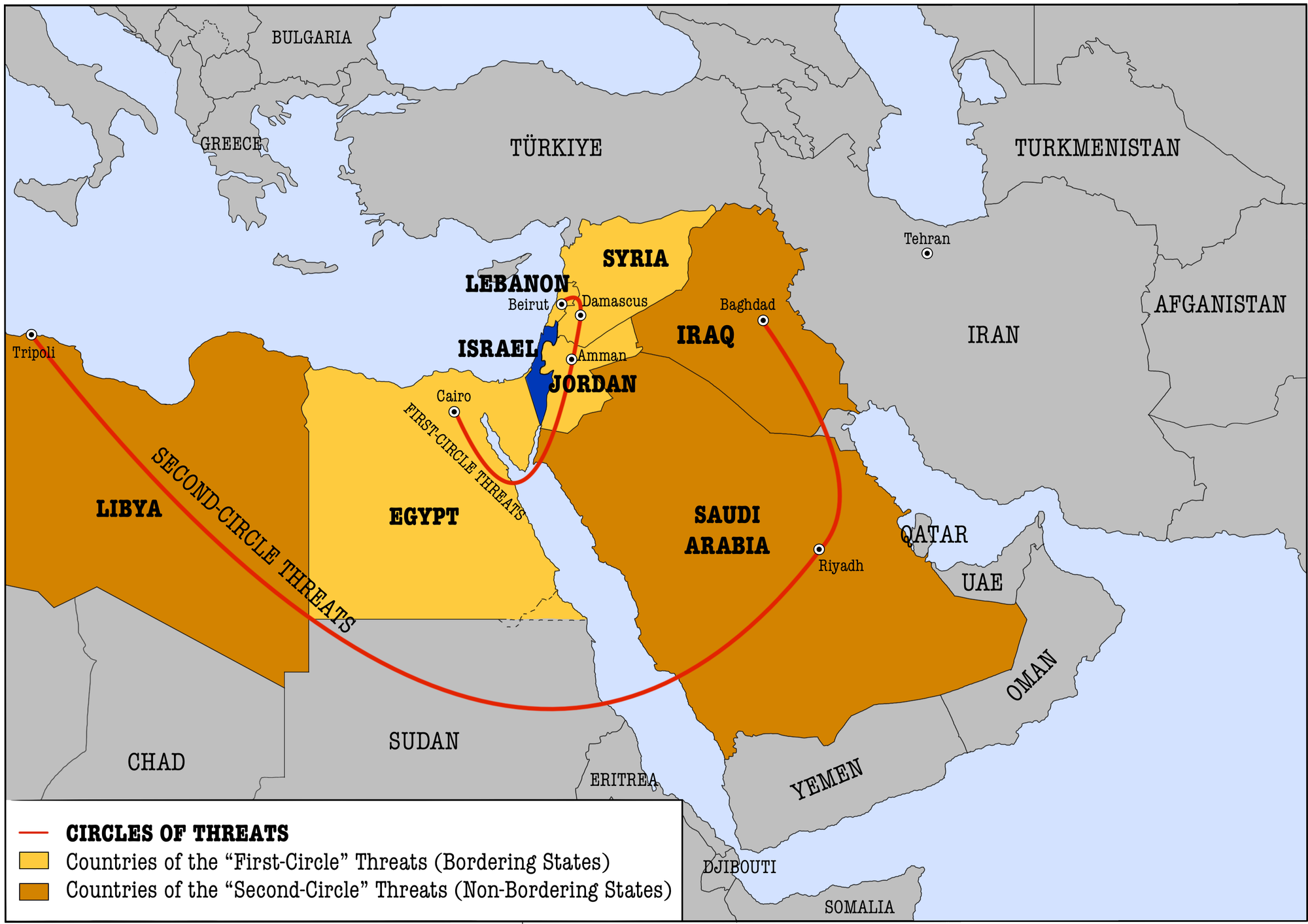

They thus distinguished two Circles of Threats (Map 1).

- First-Circle threats encompassed Israel's bordering nations, commonly referred to as confrontation states, including Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. However, Lebanon was not classified as a conventional threat due to its military weakness, but rather as a terrorism and guerrilla threat (Barak et al., 2023; Kam, 2003).

- Second-Circle threats referred to Israel’s non-bordering states, which were expected to contribute to the war effort by providing support to the confrontation states in the event of a major Arab-Israeli conflict. These peripheral Arab states primarily included Iraq and to a lesser extent Saudi Arabia and Libya (Barak et al., 2023, p.6).

2. Arab and Iranian Non-Conventional Capabilities

Non-conventional threats to Israel stem mainly from two types of non-conventional weapons: chemical and nuclear weapons.

Chemical Weapons

The state of Israel has long been deeply concerned about chemical weapons, as they have been deployed multiple times by Iraq, Syria, and Egypt (Kam, 2003, p.360). However, the probability of their use today is minimal, having Iraq ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention in 2009 and Syria in 2013. Egypt has neither signed nor ratified the Convention, while Israel has signed but not ratified (Arms Control Association, n.d.). Consequently, the likelihood of these states employing such weapons is remote, especially considering the potential retaliation from Israel.

Nuclear Weapons

The nuclear danger is posed by two states: Iraq and Iran.

- In the past, Iraq came close to achieving nuclear capability. However, its nuclear endeavours were halted by Israel's destruction of Iraq's nuclear reactor in 1981, and by the United States a decade later. Consequently, Iraq is now generally perceived as not posing a significant nuclear threat (Kam, 2003, p.360).

- In contrast, Iran's position remains uncertain. According to Ephraim Kam, "Iran is closer than any Arab country to developing nuclear weapons"(2003, p.360). Following the 1979 Islamic revolution, Iran terminated cooperation on the peaceful use of nuclear power with the West and initiated the development of atomic bomb technology, resulting in UN sanctions. In 2015, the multilateral Iran Nuclear Agreement - involving China, France, Russia, the UK, the US, Germany and the EU - known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), aimed to curb Iran's nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. However, in 2018 the United States withdrawal prompted Iran to disregard the constraints on its nuclear program outlined in the agreement. This has resulted in a current state of uncertainty and risk for the region (Arms Control Association, n.d.; Azodi, 2021).

3. Terrorism and Guerrilla Warefare

Terrorist attacks against Israel have taken various forms. Ephraim Kam, Senior Researcher (Emeritus) at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), has categorised them as including

“killing of innocent civilians and indiscriminate sabotage; guerrilla warfare against military units; attacks on communication lines; infiltration and cross-border attacks; hostage taking and hijacking; suicide bombing and indiscriminate mass assaults, and other forms of limited warfare” (2003, p.360).

These assaults date back to well before the establishment of the State of Israel, with incidents occurring as early as the 1920s, evolving into organised activities following its founding.

Two main types of terrorism and guerrilla warfare can be observed:

- those perpetrated by Palestinian groups - namely the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) - ;

- those by Lebanese Shiite factions - namely Hezbollah.

3.1. Palestinian Organisations

The PLO

The original aim of the Palestinian organisations was to eradicate the state of Israel.

The Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) - the most important and leading Palestinian organisation - stated in Article 17 of its first National Covenant that “the partitioning of Palestine in 1947 and the establishment of Israel are illegal and false regardless of the lapse of time” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1964, Art.17).

In the 1968 National Covenant, following the Six-Day War, it was also affirmed that

“Palestine with its boundaries that existed at the time of the British mandate is an integral regional unit” (Art.2), implying that there was no room for an Israeli state and that in fact “The partitioning of Palestine in 1947 [United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine as Resolution 181 (II)] and the [resulting] establishment of Israel is fundamentally null and void, whatever time has elapsed” (art.19).

Furthermore, it continued by asserting that

“Armed struggle is the only way to liberate Palestine” (Art.9), thus precluding any negotiation or compromise with israel, and that “for this purpose, the Arab nation must mobilize all its military, human, material and spiritual capacities to participate actively with the people of Palestine in the liberation of Palestine” (Art.15) (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1968).

The PLO's stance shifted towards moderation following the 1987 popular uprisings, known as the first Intifada. This uprising culminated in the Oslo Accords of 1993 and 1995, where Israel acknowledged the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, providing for the establishment of a Palestinian interim self-government in the Palestinian territories - the Palestinian National Authority (PNA, also PA). Concurrently, the PLO embraced the objective of establishing a Palestinian state within the pre-1967 borders (West Bank and Gaza Strip), thereby acknowledging Israel's sovereignty over the remaining Palestinian territory, a concept known as the two-state solution. As a result, many articles of the Covenant, which were inconsistent with the Oslo Accords, were completely or partially nullified (Barak et al., 2023, p.7).

- Nonetheless, “the radical Palestinian organisations - the so called 'front' organisations on the one hand, and the Islamic organisations on the other hand -” did not change their strategic objective, aiming for the destruction of the state of Israel and the subsequent creation of a Palestinian state encompassing all of Palestine's territory (Kam, 2003, p.360).

- Additionally, the revolutionary Intifada movement spurred the rise of a new form of Palestinian terrorism known as “fundamentalist Palestinian Islamic terrorism, led by the Hamas organisation” (Kam, 2003, p.360).

Hamas

The Islamic Resistance Movement "Hamas" is an Islamist militant group and a political party, born in 1987 during the outbreak of the first Intifada (Robinson, 2024).

Hamas Charters

Hamas calls "for the murder of Jews, the destruction of Israel, and in Israel’s place, the establishment of an Islamic society in historic Palestine" (Robinson, 2024).

The preamble of the founding Charter of 1988 already reveals the core of this movement: "Israel will be established and will stay established until Islam nullifies it as it nullified what was before it" (Maqdsi, 1993).

Hamas's "goal is to liberate Palestine and confront the Zionist project" (2017 Charter, Art.1). "Hamas rejects any alternative to the full and complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea" (2017 Charter, Art.20), this being "an integral territorial unit" (2017 Charter, Art.2).

Hamas condemns Egypt for signing peace agreements with Israel (1988 Charter, Art.32) and also refuses any "initiatives, and so-called peaceful solutions and international conferences, [as being] in contradiction to the principles of the Islamic Resistance Movement" (1988 Charter, Art.13; 2017 Charter, Art.22).

Indeed, in order to reach its goal

"Resistance and Jihad [the Holy War] for the liberation of Palestine will remain a legitimate right, a duty and an honour" (2017 Charter, Art.23) as "in face of the Jews' usurpation of Palestine, it is compulsory that the banner of Jihad be raised" (1988 Charter, Art.15) and also "raise the banner of Allah over every inch of Palestine" (1988 Charter, Art.6).

In order to fight against the "world Zionism", Hamas also calls to action "the Arab and Islamic people, and from the Muslim organizations in the Arab and Islamic regions" as they are best "prepared for the forthcoming role in the battle with the Jews" (1988 Charter, Art.32).

-- Full Charters available in Maqdsi (1993) and Wilson Center (2023) --

During the second Intifada, Hamas, along with the fundamentalist organisation Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), introduced the practice of indiscriminate mass attacks carried out by suicide bombings, resulting in the highest number of Israeli civilian casualties recorded in decades (Barak et al., 2023, p.7).

After Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, Hamas won the PNA legislative elections in 2006. The PLO party, led by the Fatah faction, rejected the election results and expelled Hamas from power in the West Bank. Meanwhile, in Gaza, Hamas emerged victorious in the civil war against Fatah militias, creating a political divide between the two Palestinian territories and establishing authoritarian rule in the Strip (Robinson, 2024). Since then, the relationship between Israel and Gaza has been marked by continuous tension. This tension led to multiple conflicts involving Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) air and ground operations against rocket and missile attacks from Hamas and other Palestinian factions like PIJ. Major conflicts occurred in 2008-9 (Operation Cast Lead), 2012 (Operation Pillar of Defense), and 2014 (Operation Protective Edge) (Barak et al., 2023, p.10).

These military operations reflected Israel's evolving threat perceptions, including the increasing threat posed by the proximity of rocket fire to Israel’s urban centres and the civilian population. Additionally, non-state actors attempted to overcome their technological disadvantages by using tunnels and low-tech methods such as balloons, kites, and multi-rotor drones, which increased the psychological and physical sense of insecurity facing Israeli civilians, especially near the borders.

The IDF faced challenges in gaining legitimacy for its operations against Hamas both domestically and internationally.

- Domestically, the limited political goals and inability to decisively defeat Hamas led to public dissatisfaction.

- Internationally, the complex nature of the conflict posed political, legal, and operational challenges.

At present, fighting is ongoing in the Gaza Strip following the terror attack carried out by Hamas on October 7, 2023, which resulted in over 1,100 Israeli deaths and more than 200 Israeli hostages, including over 30 children (Ryan & Pengelly, 2023; France 24, 2024).

3.2. Lebanese Shiite Organisation - Hezbollah

Hezbollah is a political party and an “Iran-backed Lebanese Shia militia”, an Iranian partner force which helps “Tehran project power across the region” and “train allied militias (reportedly including Hamas)” (Thomas & Zanotti, 2024; Hezbollah’s Record on War & Politics, 2023).

Its primary support originates from Iran and Syria.

- Iran provides Hezbollah with “most of its funding”, which has been “estimated to be hundreds of millions of dollars annually”, its “training, weapons, and explosives, as well as political, diplomatic, monetary, and organizational aid” (Bureau of Counterterrorism, 2022, p.275).

- Hezbollah maintains a longstanding alliance with the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, enabling the transfer of weapons from Iran to Hezbollah through Syrian territory. Additionally, the Assad regime has “provided training, weapons, and diplomatic and political support” to Hezbollah (Bureau of Counterterrorism, 2022, p.275). In turn, Hezbollah has “played a key role in assisting pro Asad forces during Syria’s civil war” (Thomas & Zanotti, 2024).

The “long-standing alliances with Iran and Syria have transformed Hezbollah into an increasingly effective military force” (Robinson, 2023).

Hezbollah’s International Activities

In the Middle East, Hezbollah is known for supplying weapons and offering training to Houthi insurgents in Yemen. Moreover, it has been reportedly shown that “Hezbollah commanders have […] assisted the Houthi campaign against international shipping in the Red Sea” (Thomas & Zanotti, 2024). The persistent presence of Hezbollah activities in Yemen prompts international observers to consider, as stated in the CTC Sentinel Report, that “the emergence of a ‘southern Hezbollah’ is arguably now a fact on the ground” (Knights et al., 2022).

Hezbollah's activities extend beyond the Middle East and reach into Europe. Hezbollah is indeed “suspected of managing the transportation and distribution of illegal drugs into the EU, dealing with firearms trafficking and running professional money laundering operations” for other criminal organisations, as reported by the European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (Europol, 2022).

Furthermore, evidence indicates the existence of ”Hezbollah operations in Africa, the Americas, and Asia” (Robinson, 2023).

It is estimated that Hezbollah's fighter count ranges between 40,000 and 50,000 units, with its arsenal of rockets, missiles, and drones exceeding 150,000 (Thomas & Zanotti, 2024).

Hezbollah's armed militias operate independently of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), depending not on the government, but on the Hezbollah political party, whose “extensive security apparatus, political organization, and social services network have fostered its reputation as ‘a state within a state’” (Robinson, 2023).

As a result, the UN Security Council, through Resolution 1701 (2006), deployed the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) to assist Lebanon in the “establishment between the Blue Line [1949 Armistice line border between Lebanon and Israel] and the Litani river [Northern of the border] of an area free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL [emphasis added]” (UN Security Council, 2006, pp.2-3). However, the failure to create this buffer zone and “Hezbollah’s continued operation in this area is a major factor in ongoing clashes with Israel” (Thomas & Zanotti, 2024) (Map 2).

Present Conflict

From October 2023 to February 2024, UNIFIL recorded nearly 9,000 projectiles fired by artillery and mortars in both directions across the Blue Line:

“Hizbullah claimed responsibility for almost daily strikes from Lebanon against Israel Defense Forces positions or personnel south of the Blue Line [in northern Israel]. The Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades of Hamas and Al-Quds Brigades of Palestinian Islamic Jihad also publicly claimed responsibility for attacks from Lebanon on northern Israel” (Secretary-General, 2024, II.A.).

The Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations stated that

“the gravity and volume of these attacks is unprecedented and includes the launching of hundreds of rockets, anti-tank missiles and mortar shells, the firing of gunshots towards Israel Defense Forces (IDF) positions, personnel and Israeli communities along the northern border, and various drone infiltrations” (Secretary-General, 2024, II.A.).

For this reason, approximately 80,000 residents were evacuated from northern communities near the Lebanese border (Dettmer, 2023) and Israeli officials have cautioned that if Hezbollah fighters are not withdrawn north of the Litani, there could be an escalation of military actions in southern Lebanon (Thomas & Zanotti, 2024).

Should the conflict ignite further, it must be considered that topographically, in this mountainous terrain, certain advantages of the Israeli army are lost, allowing smaller squads to easily challenge larger military units. Additionally, Shiite terrorism, driven by fundamentalist zealots, posed significant challenges for Israeli intelligence in infiltrating these organisations and acquiring information regarding their plans and deployments (Kam, 2003, p.360).

4. Current Israeli “Circles of Threats”

Since its establishment in 1948, Israel has meticulously assessed potential threats posed by neighbouring Arab states, basing its classifications on their proximity to Israeli civilian centres. This led to the categorisation of Arab countries into First-Circle or Second-Circle threats, depending on their geographical proximity, namely bordering or non-bordering (Map 1).

However, a shift in this classification occurred around 1991, coinciding with the emergence of Palestinian terrorism during the first Intifada (Barak et al., 2023, p.6). Following the 1967 war and the subsequent annexation of the West Bank from Jordan, Israel found itself confronted with a much more immediate threat arising within its own borders: Palestinian terrorism. At the same time, the chances of another significant conflict involving the regular armies of a coalition of Arab nations diminished, as Israel established peace treaties with both Egypt and Jordan.

- Consequently, Israeli military leaders began to perceive First-Circle threats as originating from groups and individuals committing terror attacks from within Israeli territory.

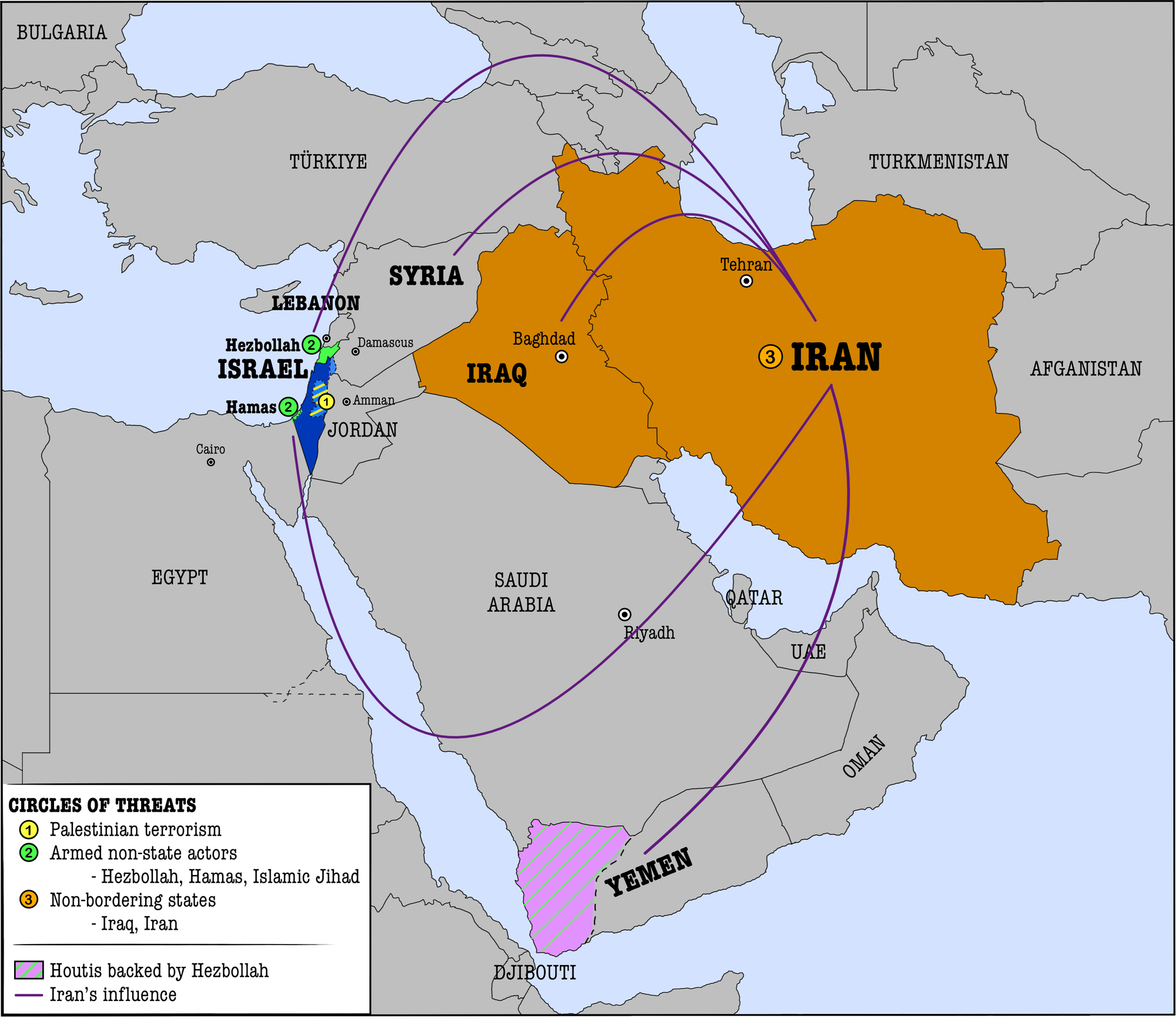

- In addition, as the threat from neighbouring states diminished, Second-Circle threats primarily stemmed from armed non-state actors, notably the emergent terrorist organisations Hezbollah, Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), which have increasingly posed significant security risks to Israeli citizens.

- Further complexities emerged with Third-Circle threats, originating from non-bordering countries. Initially represented by Iraq and Iran, today's focus predominantly shifts to Iran only, due to its alarming nuclear program, its increasing influence in the Middle East, and its support for the proliferation of proxies forming the widely recognized Axis of Resistance (Map 3) (Barak et al., 2023, pp.6-12).

The Axis of Resistance is an Iranian-led informal alliance which poses an escalating threat to Middle Eastern security. Members within the Axis, including the Syrian Assad regime, Hezbollah, certain Iraqi Shi’a militias, Hamas, PIJ, and select Bahraini militias, benefit from Iranian backing, fostering collaboration, and sharing resources to bolster their collective capabilities. Iran strategically nurtures this network to amplify its influence, utilising its allies to advance regional goals and ultimately establishing Iranian dominance over the region (Map 3) (Steinberg, 2021; Zimmerman, 2022).

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have adapted to the emergence of these new threats by creating a dedicated command structure focused on addressing the overarching Iranian menace. The "Third Circle (referring to third-circle threats) and Strategy Directorate" is staffed by personnel dedicated solely to conducting comprehensive assessments of Iran’s actions across the Middle East and formulating corresponding strategic responses (Lappin, 2021, p.5).

"With Iran’s subversive fingerprints all over Lebanon, Syria, Gaza, Iraq, and elsewhere, where it nourishes the terror armies with weapons, funding, doctrine, and training, as well as Iran’s own missile and nuclear programs, the new branch is designed to see the whole picture of Tehran’s dangerous attempts to dominate the region rather than focus on any one part” (Lappin, 2021, p.5).

📌 Key Takeaways

Categorisation based on the nature of threats

- Arab Conventional Military Capabilities: Arab states' official armies organised in coalitions including Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon.

- Arab and Iranian Non-Conventional Capabilities: Non-conventional threats include Iraq and Iran's chemical and nuclear weapons, with the latter being of greater concern due to its current ambiguous nuclear program.

- Terrorism and Guerrilla Warfare: Palestinian groups like Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) and Lebanese Shiite factions like Hezbollah pose significant threats through terrorist activities and guerrilla warfare.

Israeli Military's Classification System: Israeli military authorities classify threats into Circles based on proximity to civilian centres.

- First-Circle Threats: bordering Arab states were initially seen as primary threats, but peace treaties reduced this concern, focusing attention on internal terrorism.

- Second-Circle Threats: armed non-state actors - Hezbollah, Hamas, and PIJ - conducting terrorist activities against Israel.

- Third-Circle Threats: Iran's nuclear program and support for proxy groups, forming the Axis of Resistance, pose a major regional threat.

- Axis of Resistance is an Iranian-led alliance (Syria, Iraqi Shi’a militias, Hezbollah, Hamas, PIJ) bolstering Iran's regional influence, challenging security and stability in the Middle East.

References 📃

- Arms Control Association. (n.d.). Chemical Weapons Convention Signatories and States-Parties. Retrieved 7 May 2024, from https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/cwcsig

- Arms Control Association. (n.d.). Timeline of Nuclear Diplomacy With Iran, 1967-2023.. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Timeline-of-Nuclear-Diplomacy-With-Iran

- Azodi, S. (2021). What does the history tell us about Iran’s nuclear intentions? CSIS Next Generation Nuclear Network, 16.

- Barak, O., Sheniak, A., & Shapira, A. (2023). The shift to defence in Israel’s hybrid military strategy. Journal of Strategic Studies, 46(2), 345–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1770090

- Bureau of Counterterrorism. (2022). Country Reports on Terrorism 2022 (pp. 1–322). U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2022/

- Dettmer, J. (2023, December 6). Israel could open second front in Lebanon, defense minister hints. POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/israel-could-open-second-front-lebanon-defense-minister-hintsgaza-hamas-war-yoav-gallant/

- Europol. (2022). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2022 (TE-SAT 2022; pp. 1–96). Publications Office of the European Union.

- France 24. (2024, February 12). Who are the remaining Gaza hostages? https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20240212-who-remaining-gaza-hostages-israel

- Horowitz, S. (2023). Why Israel Is Judged Differently. Middle East Quarterly, 30(2), 1-13.

- Kam, E. (2003). Conceptualising Security in Israel. In H. G. Brauch, P. H. Liotta, A. Marquina, P. F. Rogers, & M. E.-S. Selim (Eds.), Security and Environment in the Mediterranean (Vol. 1, pp. 357–365). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55854-2_23

- Knights, M., Al-Gabarni, A., & Coombs, C. (2022). The Houthi Jihad Council: Command and Control in ‘the Other Hezbollah’. CTC Sentinel, 15(10), 1–23.

- Lappin, Y. (2021). How Israel Is Adapting to the Growing Threat of Terror Armies (Paper n°1,882). Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.

- Maqdsi, M. (1993). Charter of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) of Palestine. Journal of Palestine Studies, 22(4), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.2307/2538093

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (1964, May 28). National Covenant of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Gov.Il. https://www.gov.il/en/pages/11-national-covenant-of-the-palestine-liberation-organization-28-may-1964

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (1968, July 17). The Palestinian National Covenant. Gov.Il. https://www.gov.il/en/pages/33-the-palestinian-national-covenant-17-july-1968

- Mutawi, S. A. (2002). Jordan in the 1967 war (1st pbk. ed). Cambridge University Press.

- Ryan, J., & Pengelly, E. (2023, October 9). Hamas hostages: Stories of the people taken from Israel. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67053011

- Robinson, K. (2023, October 14). What Is Hezbollah? Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-hezbollah

- Robinson. (2024, April 18). What Is Hamas? Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-hamas

- Secretary-General. (2024). Implementation of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006) during the period from 21 October 2023 to 20 February 2024 (S/2024/222; pp. 1–25). United Nations Security Council.

- Steinberg, G. (2021). The" axis of resistance": Iran’s expansion in the Middle East is hitting a wall (SWP Research Paper, 6/2021). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik -SWP- Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit. https://doi.org/10.18449/2021RP06

- Thomas, C., & Zanotti, J. (2024). Lebanese Hezbollah (IF10703). Congressional Research Service - The Library of Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10703

- UN Security Council. (2006). Resolution 1701 (2006), S/RES/1701 (2006). https://unsco.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/s_res_17012006.pdf

- Wilson Center. (2023, October 20). Doctrine of Hamas. Retrieved 15 May 2024, from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/doctrine-hamas

- Wilson Center. (2023, October 25). Hezbollah’s Record on War & Politics. Retrieved 15 May 2024, from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/hezbollahs-record-war-politics

- Zimmerman, K. (2022). Yemen’s Houthis and the Expansion of Iran’s Axis of Resistance. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy.