Striving for Security: The Utopia of Absolute Safety

The call for security is back in the political spotlight. Although more security is called for, it is often challenging to succeed in defining what this is, and thus what is really demanded.

1. Why wonder about the Meaning of Security

What exactly drives someone to ask for more security? What, then, is sought after when asking for security? How can one provide security? How much security? And at what cost? What kind of security is being referred to? Security from whom, from what threats? And through what means?

To answer all these questions, one must first define the concept of security: what does the word security stand for?

Many different definitions have been offered over time. Indeed, due to the political, often ambiguous and inappropriate use of this word, some scholars have gone so far as to place security within the category of “essentially contested concepts” (Gallie, 1955; Buzan, 1983). This category comprises concepts whose usage and meaning would always result in disagreement, thus making it impossible to define them unambiguously.

Yet, even though it will not be possible to offer a universally accepted definition, it is still necessary to break down the concept of security into its main components in order to have some foothold to tackle the subject, since

“If we cannot name it, can we ever hope to achieve it?” (Booth, 1991, p.317).

Therefore, the work here will be to analyse the main definitions provided by scholars and combine them into a definition that is as accurate as possible. Having done so, the difference between security and survival, two often confused concepts, will be discussed.

2. Defining (National) Security

In Lippmann’s (1943) words:

“A nation is secure to the extent to which it is not in danger of having to sacrifice core values, if it wishes to avoid war, and is able, if challenged, to maintain them by victory in such a war” (p.51).

This definition, although accurate and truthful, is, however, limited to the sole military dimension, implying that a nation’s security increases or decreases according to its ability to deter an attack or defeat it.

A more comprehensive definition, encompassing other than only the military aspect of security, is proposed by Wolfers (1991):

“Security, in an objective sense, measures the absence of threats to acquired values” (p.150).

A further remark must be raised here.

Achieving security, as defined by Wolfers, becomes de facto impossible. Absolute eradication of threats is, indeed, utopian.

Although the definition of security has been broadened to include all other scenarios that do not concern the military, identifying security with the absolute absence of threats leads to a chronic impossibility of achieving such a state of security.

As a matter of fact, the challenge of how to achieve a security condition by starting with defining security according to the literal meaning of the term inevitably leads to considering security as an absolute condition.

Semantically speaking, in fact, the very word security implies an absolute condition, “something is either secure or insecure” (Buzan, 1983, p.217). Security, just like power, “does not lend itself to the idea of a measurably-graded spectrum like that which fills the space between hot and cold” (Buzan, 1983, p.217).

At best, one may say that something is more secure or less secure with respect to something else, but that cannot be measured. Indeed, security is a value “of which a nation can have more or less and which it can aspire to have in greater or lesser measure” (Wolfers, 1952, p.484).

The definition provided by Mroz (1980) appears to take into account what has been said so far, avoiding absolutist bias:

“Security is the relative freedom from harmful threats” (p.105).

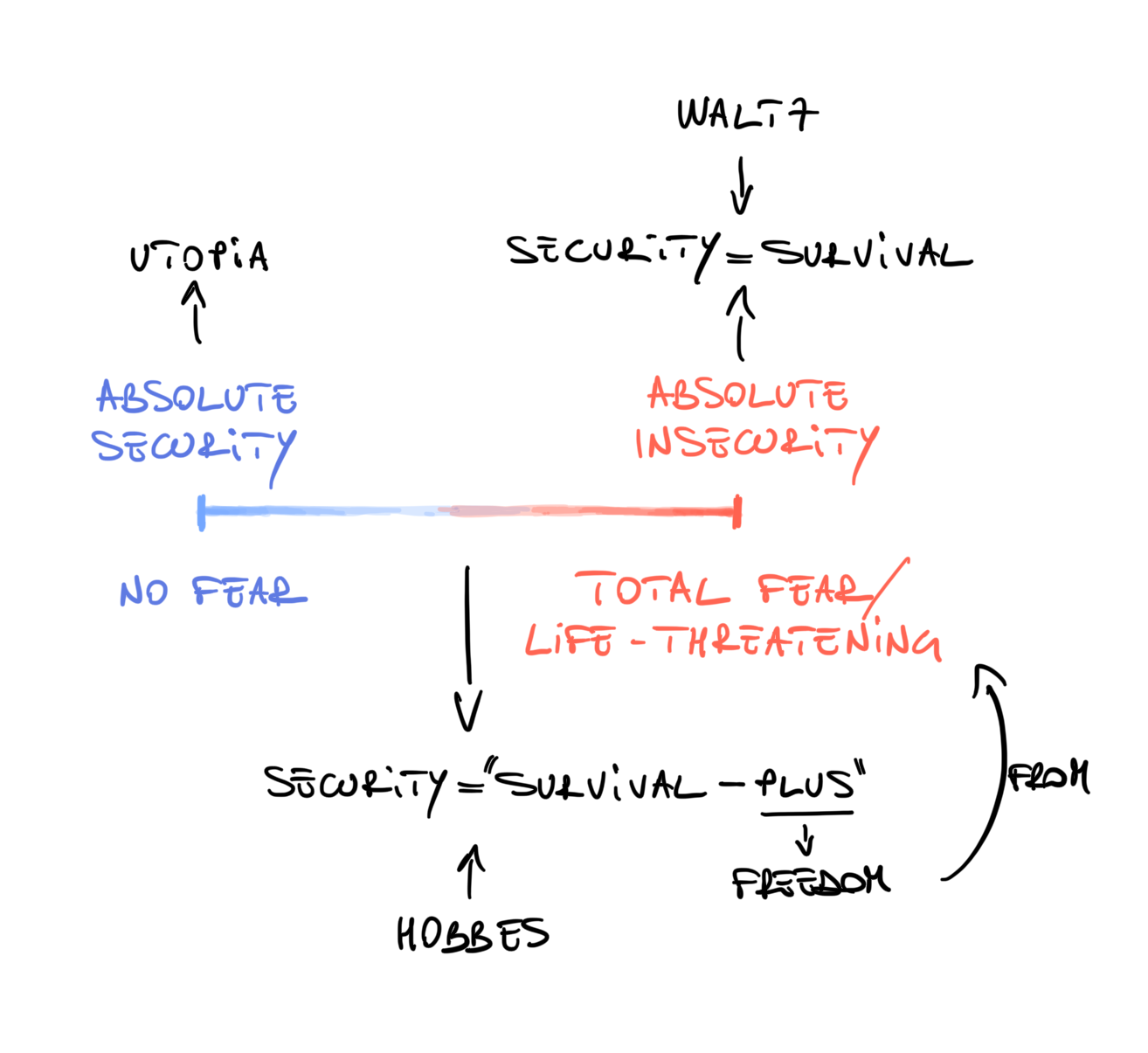

Such a definition thus suggests the always relative nature of security: absolute security is a dream, a utopia as it would entail absolute freedom from any fear (Booth, 2007, p.105).

Furthermore, this also brings up the subjective nature of security: it is possible to feel secure without being secure.

The subjective aspect of security is also taken up by Wolfers (1991), who further specifies that security “in an objective sense, measures the absence of threats to acquired values, in a subjective sense, the absence of fear that such values will be attacked” (p.150).

Similarly, Baldwin (1997) proposes a rewording of the phraseology used by Wolfers, also including the immeasurable character of security:

Hence, security cannot be achieved in its absolute form. What can be achieved is a condition or a feeling of greater or lesser security, this being defined as a low probability of threat and damage to acquired values.

3. Does Security Equal Survival?

Security and survival are terms that are placed next to each other so much so that, on some occasions, the two words are even used as synonyms.

However, these frequently refer to different scenarios.

Kenneth Waltz (1979/2010) asserts the existence of an equation between security and survival:

“In anarchy, security is the highest end. Only if survival is assured can states safely seek such other goals as tranquility, profit, and power” (p.126).

Waltz argues that in a state of anarchy, and thus in a climate of uncertainty resulting in perpetual danger of war, survival, which should normally be taken for granted, becomes the priority.

According to Waltz, therefore, security comes to coincide with the survival of the state and its citizens, since, in a climate of absolute uncertainty, the highest degree of security to which states can aspire is “enough to ensure survival” (Baldwin, 1997, p.21).

Nonetheless, survival is an existential condition - it means continuing to exist - and therefore the two terms cannot be considered synonymous in absolute terms.

What is the difference, then, between survival and security?

Tracing back to Hobbes’s (1642/1998) writings, he identifies security as the supreme law. In On the Citizens, he indeed states:

“The safety of the people is the supreme law” (Chapter XIII, 2). Yet, how should safety be interpreted? He goes on to argue that “by safety one should understand not mere survival in any condition, but a happy life so far as that is possible” (Chapter XIII, 4).

As opposed to Waltz, who draws an equation between security and survival, Hobbes believes that security is something more than mere survival. To use Booth’s (2007) words, security can be defined as “survival-plus” - “the plus being some freedom from life-determining threats, and therefore space to make choices” (p.102).

The very etymology of the word - from Latin: se (without) + cura,ae (anxiety, worries, dangers) → securus,a,um - suggests this interpretation.

Thereby, the difference between the two terms appears to be clear:

“Survival means being alive, security means living” (Booth, 2007, p.107).

Finally, echoing the definition for which security measures “in a subjective sense, the absence of fear that such values will be attacked” (Wolfers, 1991, p.150), it can be said that when security comes to coincide with survival is when there is a total fear that fundamental values, such as the value of one’s own life, are in danger, and one is therefore in a situation of total insecurity.

📌 Key Takeaways

- Absolute security does not exist, since it implies the absolute absence of threats, objective or perceived as such. Indeed, it also implies the total absence of fear, which is impossible to achieve.

- Measuring security depends on the perception of the measuring subject. Accordingly, a distinction can be made between subjective and non-subjective security; the first being what one experiences at the moment, and the latter what history and retrospect show, or what a hypothetical omniscient entity may have known at the time.

- There is a difference between security and survival. Security can also be defined as survival-plus, where the plus is the “choice that comes from (relative) freedom from existential threats” (Booth, 2007, p.106)

✍️ With a Sketch

References 📃

- Baldwin, D. A. (1997). The concept of security. Review of International Studies, 23(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210597000053

- Booth, K. (1991). Security and emancipation. Review of International Studies, 17(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210500112033

- Booth, K. (2007). Theory of world security (Vol. 105). Cambridge University Press.

- Buzan, B. (1983). People, states, and fear: The national security problem in international relations. Wheatsheaf Books.

- Gallie, W. B. (1955). Essentially Contested Concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56, 167–198. JSTOR.

- Hobbes, T. (1998). On the citizen. Cambridge University Press.

- Lippmann, W. (1943). U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic. Little, Brown & Co.

- Mroz, J.E. (1980) Beyond Security: Private Perceptions Among Arabs and Israelis. New York, International Peace Academy.

- Waltz, K. N. (2010). Theory of international politics (Reiss). Waveland Press. (Original work published 1979)

- Wolfers, A. (1952). “National Security” as an Ambiguous Symbol. Political Science Quarterly, 67(4), 481–502. https://doi.org/10.2307/2145138

- Wolfers, A. (1991). Discord and collaboration: Essays on international politics (9. print). Johns Hopkins Univ. Pr.