How to Deal with the Prospect of War: The Role of Deterrence and Defence

When faced with a hostile nation wishing to strike against it, a State has two options: Deter the adversary and avoid conflict, or prepare for Defence and War.

How to Deal with the Prospect of War: The Role of Deterrence and Defence

The air is thick with tension.

In the heart of the capital, the military headquarters buzzes with activity. Soldiers clad in camouflage uniforms move purposefully through the compound, their faces stoic, reflecting the gravity of the impending conflict.

Strategists huddle over maps and blueprints in the war room, meticulously planning every move. Commanders bark orders into radios, coordinating the deployment of troops and resources. Intelligence officers sift through information, gathering crucial data about the enemy’s strengths and weaknesses.

On the outskirts of the city, massive transport planes and helicopters roar over the runway, ready to ferry troops and supplies to the front lines.

Meanwhile, on the home front, civilians rush to stock up on essentials, their faces carved with anxiety. Families gather in makeshift shelters, seeking refuge from the uncertainty that looms overhead. The streets are eerily quiet, except for the occasional rumble of military convoys passing through.

In the midst of this organized chaos, the state leaders address the nation, rallying citizens with speeches of unity and resolve. The flag flies at half-mast, a sombre symbol of the gravity of the situation.

No one is safe.

The scene paints a stark picture of a nation preparing itself for the seemingly inevitable clash, a picture of preparation where every gear in the war machine works in unison, driven by a sense of duty and a determination to defend their homeland.

A clash that must nevertheless be evaded.

Two potential scenarios have been therefore taken into consideration by the commanders-in-chief.

- The first sees the success of the implementation of their deterrence strategy leading to the avoidance of war.

- The second involves going to war and thus having to prove their defence strategy to be successful.

. . .

The purpose of this article is to provide a primary explanation of how the two strategies work and how they interplay with each other. The organisation is as follows:

- Defining: Clear definitions of each of the two concepts, deterrence and defence respectively, are provided.

- Comparing: The functioning of deterrence and defence strategies are compared, making two respective examples explicative of their differences.

- Analysing over time: Differences and commonalities between the two strategies are analysed over time.

- Limited Retaliation: A special case where deterrence and defence coincide in time is analysed.

1. Defining Deterrence and Defence

1.1. Deterrence

Deterrence is defined as

“the practice of discouraging or restraining someone from taking unwanted actions, such as an armed attack” (Mazarr, 2021, p.15).

The way this practice is carried out is

“by posing for him [the potential attacker] a prospect of cost and risk outweighing his prospective gain” resulting from an armed attack (Snyder, 1961, p.3).

The deterrence strategy thus seeks to act on the enemy’s intentions so as to make him change his mind, thus avoiding direct warfare (Snyder, 1961, p.3).

1.2. Defence

On the other hand, instead of acting on the enemy’s intentions, defence seeks to act on its military and otherwise capabilities to harm or damage us (Snyder, 1961, p.3).

Defence can be defined as the practice of protecting ourselves and resisting the enemy’s assault so as to minimise our losses.

2. Deterrence and Defence Strategies Compared

The differences between deterrence and defence can be simplified into 3 categories:

- their purpose

- their time frame

- their military means

Having already discussed their purpose, the following is an analysis of the other two

2.1. Timing

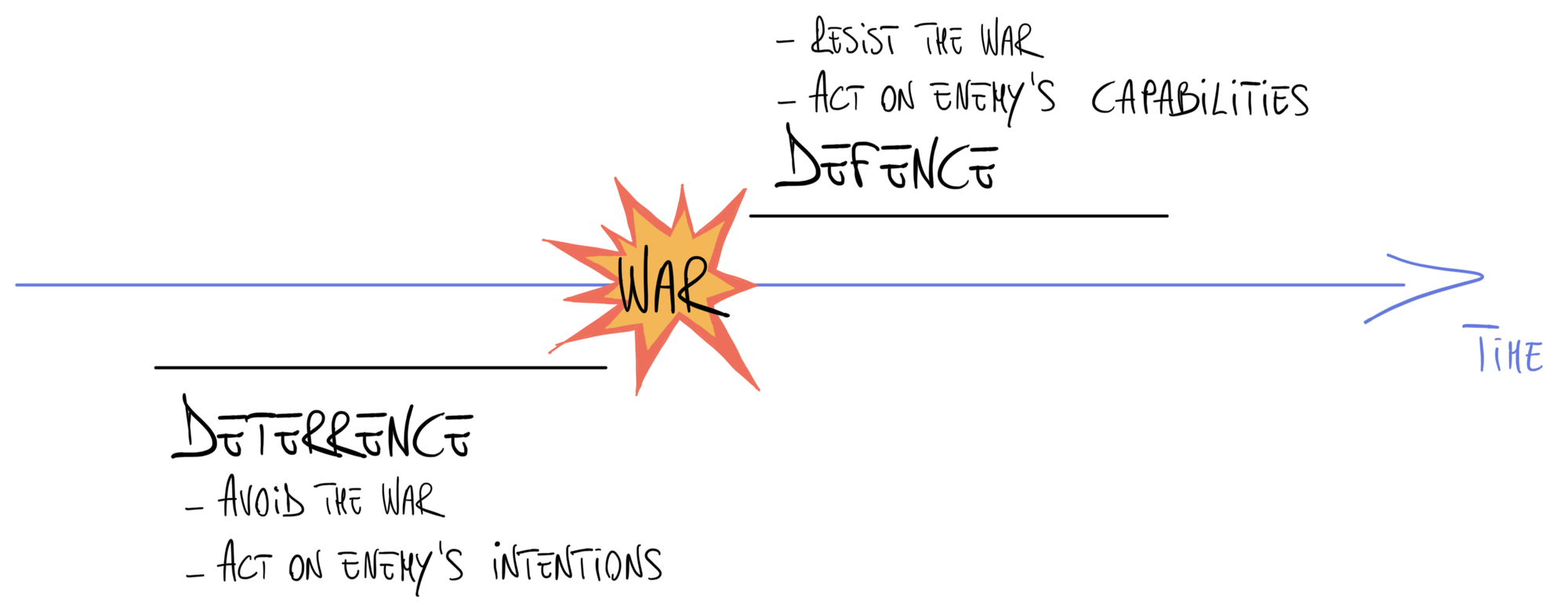

As a consequence of their different purposes, the second fundamental difference between the two strategies is their employment over time.

Indeed, the role of defence comes into play when deterrence fails.

The difference between the two notions becomes even clearer when referring to Clausewitz’s definition of the concept of defence and its characteristic features, respectively: “the parrying of a blow” and “awaiting the blow” (Von Clausewitz, 1832/2007, p.159).

Here, the temporal difference between the two strategies becomes explicit:

- The value of deterrence is to be appreciated in peacetime, when it seeks to prevent war, while the value of defence in wartime.

- The moment the first fails, and thus war breaks out, the second comes into play, whose purpose is to reduce our costs.

2.2. Military Means

It might be trivial to think that a given capability of the defence forces also has a deterrent effect against an enemy, yet this could be a fallacious deterrent strategy.

Using the same military forces to defend against and to deter the enemy in fact could be effective as well as it could turn out to be a total failure.

Outlined below are two strategies, respectively for defense and deterrence, which are not interchangeable, and should they be used for both purposes, they would fail.

Defence Strategy

As already mentioned above, a successful defence strategy must resist the enemy's assault so as to minimise our losses.

- For instance, a good defence strategy, given a large military advantage on the part of the attacker against the defender, could be to minimise the casualties in terms of men and lost territories, so as not to compromise national integrity.

- Such a defence strategy, however, would be a poor deterrence one towards the attacker, who would be certain of the conquest over certain territories, and who would then carry out the attack.

The opposite is also true: as outlined below, a great deterrence strategy could be a terrible defence one.

Deterrence Strategy

The war that deterrence forces strive to fight is psychological warfare: they try to dissuade the enemy from engaging in combat by altering his cost-benefit calculations so that the costs turn out to be greater than his possible gains on the ground.

It is not necessarily the case that such forces, despite being able to deter the enemy from engaging in the attack, would also have been able to successfully defend it.

For deterrence to work, deterrent forces must potentially inflict the “minimum unacceptable damage” such that the enemy would be discouraged from launching the attack, and thus it would not take place (Snyder, 1961, p.5).

- Given the same military asymmetry in favour of the attacker, such unacceptable minimal damage could be, for example, the destruction of the enemy’s capital city through long-range missiles. If, therefore, we, the deterrer, were capable of such destruction and threatened the attacker to carry it out should he decide to attack, the enemy would be deterred as he could not endure such destruction, and the war would thus be avoided.

- Should this strategy fail, and the attacker still decides to launch the attack, the same would be completely useless in defending ourselves. Indeed, it would paradoxically stimulate the enemy to inflict further damage against us, thus resulting in additional costs to us and in no way helping to defend ourselves and win the war, although the psychological element of the threat would not disappear entirely.

3. The Evolution of Deterrence and Defence Strategies

Although it is often associated with nuclear weapons and thus with the Cold War period, the theory of deterrence has much more distant origins that can be traced back to thinkers such as Carl von Clausewitz.

As wisely remarked by Brodie (1959), in fact, “the threat of war, open or implied, has always been an instrument of diplomacy by which one state deterred another from doing something of a military or political nature which the former did not wish the latter to do” (p.174).

However, the difference between defence and deterrence was not as marked as it is today: the weapons and strategies used for defence were roughly the same as those used for deterrence.

The evolution of deterrence and defence strategies sees three fundamental steps:

- Overlapping Strategies

- Employing the Same Military Means

- Emerging New Technologies

3.1. Overlapping Strategies

In his masterpiece On War of 1832, written before the advent of modern weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and long-range weaponry, Von Clausewitz does not explicitly discuss deterrence, as it is a strategy aimed at preventing war and is therefore used before war breaks out.

Nevertheless, “conventional deterrence is rooted in the Clausewitzian logic of war, which comprises physical, moral, and psychological factors. All tend to favor defense followed by offense in an overall deterrent posture” (Chiabotti, 2018, p.14).

Moreover, also Clausewitz (1832/2007), in reviewing the interaction that exists between attack and defence, analyses elements such as fear, danger, the moral factor and reputation.

These are the same elements that play a decisive role in a successful deterrence strategy.

Indeed, “as fear of our strength has prevented him [the attacker] from entering our theatre of operations or seeking out our position or has caused him to avoid the battle we are prepared to give, the objects of the defence have been accomplished” and the deterrence strategy succeeded (Von Clausewitz, 1832/2007, p.175).

3.2. Employing the Same Military Means

In conventional warfare, where no WMD are allowed, the primary functions of military forces, “to punish the enemy, to deny him territory (or to take it from him), and to mitigate damage to oneself”, can be performed by the same conventional weapons (Snyder, 1961, p.8).

3.3. Emerging New Technologies

As shown in the examples above, it can be observed that the need to clearly distinguish between deterrence and defence strategies stems from the invention and spread of new military technologies, such as long-range and nuclear weapons, as these have a predominantly deterrent value and are not usually used as defensive weapons.

When referring to conventional deterrence, defined by John Mearsheimer (1983) as “a function of the capability of denying an aggressor his battlefield objectives with conventional forces”, hence excluding nuclear weapons, this distinction is more nuanced (p.15).

. . .

To sum up what has been said so far:

- The defence strategy may be the same to have a deterrent effect.

- The two strategies may also make use of the same military means to achieve their purpose.

- However, they are always employed at a different moment in time:

- the deterrence strategy is used and carries out its effects before the conflict breaks out, while the defence strategy operates after the conflict escalates.

The only exception to this pattern is the case of limited retaliation.

4. When Deterrence and Defence Coincide in Time: The Case of Limited Retaliation

In the Nuclear Era, there might be a singular situation where defence and deterrence coincide in time. In this case, the weapons of defence and deterrence might also be the same.

The strategy of limited retaliation can be used when a state with smaller military forces is pitted against a state with disproportionately larger military forces.

The deterrent strategy of nuclear threat having failed because lacking in credibility, the weaker state has to make its defensive moves.

What it can do in this circumstance, in addition to its normal defence, which can in no way withstand a continuation of the fight, is to persevere with its deterrence posture and strategy, making it more concrete:

The purpose of the limited retaliation strategy is to

“coerce its adversary into backing down by inflicting a limited amount of punishment in order to make the threat of future punishment sufficiently credible that the adversary no longer finds it worthwhile to continue the confrontation” (Powell, 1989, p.503).

- Its aim is not to punish the enemy for the transgression of the initial warning but rather to demonstrate that he is actually able to carry out the deterrence threatened at the outset.

- In this way, the threatened damage is effectively inflicted, slowly, without unnecessarily provoking the enemy through disproportionate damage that would trigger his equally disproportionate and destructive reaction.

- Strike after strike would realise in the enemy the idea of receiving all the threatened damage.

- Territorial defence, added to the psychological warfare of deterrence through limited retaliation, would ensure the swift conclusion of the war because of the prospect of unacceptable costs rather than the failure of military action.

Limited retaliation proves to be a means as much for deterrence as for defence, bridging “this dichotomy by using the threat to inflict punishment both as a means to deter the beginning of the war, and as a means of ending it on acceptable terms” (Snyder, 1961, p.194).

Therefore, although defence and deterrence are two different concepts, and often occur at different times, it may happen that deterrence may be used as a defence strategy in a conflict that has already begun.

In this case, the use of deterrence would continue even during the actual war in order to bring about its end more rapidly without escalating into further fighting (Snyder, 1960).

📌 Key Takeaways

- A defence strategy and its means can also be used for a deterrence strategy, however, this may not always be successful. Indeed, the distinction between deterrence and defence strategies became crucial with the advent of new military technologies like long-range and nuclear weapons, as they have a predominantly deterrent value and are not usually used as defensive weapons.

- An exception is the strategy of Limited Retaliation, which involves a controlled use of the nuclear capacity to coerce the adversary into backing down and aims to demonstrate nuclear deterrence credibility as well as end the war with acceptable terms. It is a unique scenario where defence and deterrence coincide in time.

References 📃

- Brodie, B. (1959). The Anatomy of Deterrence. World Politics, 11(2), 173–191.

- Chiabotti, S. D. (2018). Clausewitz as Counterpuncher: The Logic of Conventional Deterrence. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 12(4), 9–14.

- Mazarr, M. J. (2021). Understanding Deterrence. In F. Osinga & T. Sweijs (Eds.), NL ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2020 (pp. 13–28). T.M.C. Asser Press.

- Mearsheimer, J. J. (1983). Conventional Deterrence. Cornell University Press; JSTOR.

- Powell, R. (1989). Nuclear Deterrence and the Strategy of Limited Retaliation. American Political Science Review, 83(2), 503–519.

- Schelling, T. C. (1965). Controlled response and strategic warfare. The Adelphi Papers, 5(19), 3–11.

- Snyder, G. H. (1960). Deterrence and power. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 4(2), 163–178.

- Snyder, G. H. (1961). Deterrence and Defense. Princeton University Press.

- Von Clausewitz, C. (2007). On War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.